Classic batteries and the development of (electro)chemistry

History of Technology - The Discovery of Nanoworlds Enables Renewable Energy Supply for All / Episode 16

Translation from the German original by Dr Wolfgang Hager

Electrochemical electricity storage systems, batteries, are crucially important for a sustainable energy transition. Their rapid development over the last twenty years - made possible by new developments in materials science based on quantum theory - has opened up previously undreamed of possibilities. But the origins, without which their functioning cannot be understood, go back much further. In this instalment, we first look at the development of traditional batteries, which in turn is closely linked to the development of chemistry during industrialisation.

Fuels such as wood, coal or oil can be stored and transported at a manageable cost. This is more difficult with electricity: it is not a substance. Electric or magnetic fields can be stored in capacitors or coils only at considerable expense. Electrical energy must essentially be used the moment it is generated. To store it, it must be converted into other forms of energy. This can be done in pumped storage power stations, for example, where it is stored in the form of mechanical potential energy, which is then converted back into electricity in water turbines with generators. However, since the early days of its utilisation, electricity has also been stored in the form of chemical energy: In electrochemical reactions, electricity can be generated by combining and transforming different substances and, in rechargeable batteries, the reaction can be reversed by introducing electricity. Depending on the process, the reactions can take place very efficiently and with almost no heat loss. Initially, batteries were the only viable source of electricity; electromechanical power generation had not yet been invented. After the advent of generators, rechargeable lead batteries were used to compensate for fluctuations in small grids. Later, mobile applications of batteries in vehicles and small appliances took centre stage. Much more powerful and cheaper, they are now becoming an indispensable element of a comprehensive electrification of the energy supply, both for mobile and stationary applications. They offer transportable electricity and buffer storage at all levels. Only with new types of batteries available for some years, will it be possible to achieve this transition to a fully renewable energy supply.

Lithium-ion batteries have been the centre of attention for some years: first for mobile electronic devices, then for electric cars and increasingly as day/night storage in the power grid. Since the turn of the millennium, their energy density has quadrupled, while costs have fallen by 93%. In contrast, the lead-acid battery, inferior in many aspects, has hardly changed in the 150 years of its history. Where does this difference come from? For how long can the trends in performance and costs continue like this?

Similar to photovoltaics (see episodes 11 and 12 of this series), this accelerated development is due to advances in materials science based on quantum theory. Due to the greater complexity, however, the new developments in the battery sector did not start until later. Because of their far-reaching consequences — not only for batteries — it is worth taking a closer look at these developments.

My article series on the history of energy technology:

The discovery of nanoworlds enables a renewable

energy supply for allThe episodes so far:

Nuclear fission: early, seductive fruit of a scientific revolution

Where sensory experience fails: New methods allow the discovery

of nano-worldsSilicon-based virtual worlds: nanosciences revolutionise information technology

Climate science reveals: collective threat requires disruptive overhaul of the energy system

The history of fossil energy, the basis of industrialisation

The climate crisis is challenging the industrial civilisation: what options do we have?

Nanoscience has made electricity directly from sunlight unbeatably cheap

Photovoltaics: Increasing cost efficiency through dematerialisation

50 years of restructuring the electricity system — From central control to network cooperation

Emancipation from mechanics — the long road to modern power electronics

Power electronics turns electricity into a flexible universal energy

This instalment deals with the development of traditional electrochemical batteries and the discovery of their chemical and electrochemical foundations during industrialisation, initially mainly in Europe. The next instalments will deal with the emergence of modern materials science, which in turn will help us to understand the significance and prospects of the lithium-ion battery and other new battery concepts.

The beginnings: Volta's battery revolutionises chemistry

The triumph of electricity and chemistry began with an electrochemical battery: with the invention of the zinc-copper battery by Alessandro Volta in 1799 and its publication the following year, a reliable power source for experiments with electric currents was now available for the first time. Volta was inspired by the experiments of Galvani, who had used metal electrodes to make frogs' legs twitch and postulated "animal electricity". By stacking many pairs of zinc and copper plates separated by a felt soaked in salt water, the widely travelled Lombard aristocrat and rector of the University of Pavia was able to generate an electric current between the contacts at the top and bottom of his "Voltaic Column" that lasted no more than an hour. He thus proved that electricity could be generated chemically. He had previously arranged a series of metals according to the order in which pairs of metal trigger a voltage (tingling) on the moist tongue. In Volta's column, the voltages of the individual metal pairs added together.

The very same year, 1800, William Nicholson, Anthony Carlisle and Johann Wilhelm Ritter invented electrolysis: they decomposed water by conducting electricity from Volta's battery through salty water, forming hydrogen on one and oxygen on the other electrode. This already showed that electricity could have practical uses. Early industrialisation, the fruit of technical inventions, increasingly motivated young people all across Europe to take an interest in science and technology.

Using the voltaic source for current, the English chemist Humphry Davy then laid the foundations for further advances. By means of electrolysis, he was the first to produce quite a number of elements (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, strontium, barium) in pure form. While Volta still believed that electricity was generated solely by the contact of two metals, Davy clearly demonstrated that the battery's voltage was generated by a chemical process between the electrolyte (in Volta's battery, the salt water in the felt) and the adjacent metals.

At the same time, Dalton, Gay-Lussac and Avogadro working on gases showed that matter actually consists of atoms that can combine to form molecules following certain rules. This was consistent with Davy's electrochemical results. Within a few years, it was possible to categorise the known elements according to their atomic mass, which was given as a multiple of the hydrogen atom, and also to determine for many molecules which atoms they were made off. This made it possible to draw up reaction equations.

Michael Faraday, one of the most influential researchers in the history of science, who is best known for his groundbreaking findings on electromagnetism, was a student of Davy and also worked intensively on electrochemistry. Following his discovery in 1833 that moving magnetic fields could be used to generate electricity, Faraday started by proving that the electrical energy so generated had the same effects as the electricity from Volta's battery, or the electricity generated by friction in the eighteenth century.

Afterwards, he focused more closely on electrolysis. With his rigorously quantitative approach, he soon discovered the "Faraday laws of electrolysis": firstly, the amount of substance deposited is proportional to the electrical charge passed through it. Secondly, the mass of substance deposited by a certain amount of charge is proportional to the atomic weight of the corresponding element and inversely proportional to its valence (number of monovalent atoms, e.g., hydrogen, that the atom can bind). This proved that electrical energy is converted into chemical bonding energy during electrolysis. Conversely, chemical bonding energy is converted into electrical energy in the battery. When a compound is formed, the chemical energy is released as electrical energy, and vice versa. The actual processes in a battery are bit more complicated, as several electrochemical processes can take place between the elements present, superimposed on each other.

Electrochemical membranes open the door to the worldwide spread of telegraphy

Although nothing was known at the time about the existence of electrons - negative charge carriers that are not necessarily bound to atoms - and about the conduction mechanisms in metals, Faraday's findings were sufficient to develop a variety of batteries with different combinations of electrodes and electrolytes. Batteries were the only viable sources of electricity at the time. They were used for experiments and for the first telegraphs.

A particularly important step was the prevention of hydrogen formation, which occurs simultaneously with the main reactions in the Volta battery. In 1836, John Frederick Daniell constructed the Daniell element, in which the conversion of copper ions into copper and the conversion of zinc into zinc ions takes place with different electrolytes separated by a porous wall permeable to negative ions. This significantly extended service life compared to the Volta battery. More generally, this invention of a selectively permeable membrane paved the way for many later developments.

This more powerful power source made it possible for the first applications of electricity to become established in practice. For decades, variants of the Daniell elements became the preferred power source in telegraphy, as it was not until the 1870s that electromagnetic generators were able to supply electricity, although these were still not generally available.

With these developments, by 1840, the physico-chemical discoveries that formed the basis for battery development over the following hundred years had essentially been completed. What followed were primarily technical refinements and massive industrial implementation.

Democratic England as the centre of development

At this time, London was the undisputed centre of scientific and technological development. The Industrial Revolution began in England. Many historians see its origins in the English Revolution of the 1640s, which was largely inspired by the ideas of Descartes and Bacon.

Isaac Newton (1642-1726) was one of the founders of modern science with his major work "Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy". His classical mechanics, his infinitesimal calculus and his contributions to optics opened up completely new perspectives not only for science, but also for technology. As early as the 17th century, coal was mined for iron production and heating due to an increasing shortage of wood. Around 1750, mining tunnels at a depth of 50 metres were common. In 1815, coal was already supplying 83% of energy consumption in England and Wales, compared to just 11% in Germany and 5% in France. At the time of the unification of Italy in 1861, coal accounted for only 7.5% of the energy supply there, compared to 45% in France.

In 1712, a steam engine was used for the first time in a coal mine, which James Watt improved so significantly in the 1760s that it was used worldwide. In 1785, the first mechanical loom was built, which was improved over time by numerous inventors, driven by steam engines from 1790 and finally fully automated in 1834. On the one hand, many skilled, often self-employed weavers lost their jobs, which led to riots. On the other hand, a powerful textile industry sprang up, particularly in Manchester.

The Royal Society for Improving Natural Knowledge, founded in 1660 and still in existence today, was a scientific society to which scientists from all over the world sent their reports — including Alessandro Volta on his invention of the first usable battery. In 1800, the Royal Institution was founded, a teaching and research organisation that has produced a total of 15 Nobel Prize winners.

The 12th installment of our series ("Big was beautiful...") already cited comparative research by historian Margaret C. Jacob, who found that in the 18th century in England — unlike in France — scientific knowledge was also taken up in the artisan milieu. She found illustrations of weavers reading Newton's works alongside their work. In fact, it is striking that celebrated scientists like Humphry Davy, John Dalton and Michael Faraday all came from families of craftsmen. They worked their way up to international renown being both curious and practical, in some cases as self-taught scientists. This was not the case for the leading chemists and physicists who were at the centre of developments in Germany half a century later: they mostly came from academically educated upper middle-class circles.

The salonnière Jane Marcet, who was born in London as one of twelve children of a wealthy Geneva businessman and banker, made a significant contribution to the development of chemistry at the beginning of the 19th century. She presented the latest discoveries of the prominent guests of her salon in popular pamphlets with her own drawings. Her "Conversations on Chemistry, Intended More Especially for the Female Sex", published in 1805, was widely circulated, fueling young women's interest in science and also inspiring the young Faraday to pursue scientific research.

The triumph of the lead-acid battery: the first rechargeable battery

In 1864, the Prussian army physician Wilhelm Joseph Sinsteden developed the first model of a lead battery during electrolysis experiments: he noticed different changes in the surface of two lead plates immersed in sulphuric acid to which he applied a voltage. After reversing the polarity of the applied voltage several times, two states emerged: In the charged state, lead oxide formed on one electrode and the other electrode consisted of pure lead, while the sulphur was completely bound in the sulphuric acid - a voltage of around 2 volts could be measured and utilised between the electrodes. When discharged, he found a layer of lead sulphate on the surface of both electrodes and the sulphuric acid was highly diluted. This made it possible to store electrical current chemically.

Primary batteries generate electricity consuming the chemical energy originally deployed. In contrast, so-called secondary batteries or accumulators, like lead batteries, can be recharged using external power.

In 1869, the Parisian physicist Gaston Planté further developed the lead accumulator so that it could be used in practice. However, there was hardly any demand for it. This only changed twenty years later, when electric generators were able to supply electricity and Camille Alphonse Faure in Paris achieved significant improvements of the battery that made industrial production possible. Shortly after Trouvé and Planté presented a battery-powered tricycle in 1881, Faure's battery was also used to power vehicles. The first real electric car was built by engineer Andreas Flocken in Coburg in 1888.

Once vehicles with internal combustion engines had replaced electric cars at the beginning of the 20th century, the lead-acid battery was used primarily as a starter battery; and, for a long time, also in stand-alone power grids that were not integrated into large, load-balancing interconnected grids (e.g. on islands or in West Berlin). Lead batteries were of great importance for submarines during the First and Second World Wars. In 2023, the global market for lead batteries was worth 46 billion dollars and it continues to grow. Lead-acid batteries are robust, cost-effective and can provide relatively high power for short periods. However, their energy density — both in terms of weight and volume — is significantly lower than that of newer battery types.

Atoms, molecules and the development of classical chemistry

The development of batteries and the development of chemistry are very closely linked. In the 19th century, chemistry made enormous progress with the help of physics, leading to the rise of major industries. In its first decade, it became accepted that matter was indeed made up of atoms. In 1811, Amedeo Avogadro, who had made a significant contribution to this, was the first to clarify the difference between atoms and molecules - the combination of several atoms. As early as 1704, Newton surmised that chemical processes are triggered by a force between particles (atoms) that is extraordinarily strong at close range but barely noticeable at a greater distance. Only gradually did experiments clarify which substances are chemical elements and which are compounds. Relative atomic weights of the elements and compositions of molecules were clarified via the proportions, and rules were sought as to which compounds are possible.

The chemist Edward Frankland, a specialist in metal-organic compounds and water quality, established the concept of valence of atoms in 1852 by establishing that an atom can always form the same number of bonds with other atoms. Soon afterwards, August Kekulé, inspired by Alexander Butlerow, formulated his theory of chemical structures, which formed the basis for the rapid development of organic chemistry. Parallel to Archibald Couper, he had established that a carbon atom can form four bonds, including double bonds. He soon adopted Couper's idea — which seems banal to us today — of representing bonds by dashes rather than brackets. Kekulé's structural formula for benzene, a ring-shaped carbon structure with alternating single and double bonds, was decisive for the development of industrial aromatics chemistry, which resulted in widespread products (tar colours, fuels, TNT, polystyrene, nylon...).

In 1873, James Clerc Maxwell, the most important mathematical physicist between Newton and Einstein, stated in a lecture that became famous: “An atom is a body which cannot be cut in two. A molecule is the smallest possible portion of a particular substance. No one has ever seen or handled a single molecule. Molecular science, therefore, is one of those branches of study which deal with things invisible and imperceptible by our senses, and which cannot be subjected to direct experiment.” Maxwell and subsequently Boltzmann succeeded in proving that the macroscopic laws of thermodynamics can be derived from probability considerations of molecular movements ("statistical mechanics"). It was not until 1909 that the existence of molecules was considered physically proven.

With the growing wealth of experience from chemical reactions and physical measurements, it had become increasingly clear which substances were to be regarded as elements, what their atomic weight was and to which other elements their chemical behaviour resembled. Over the course of time, this led to constantly new attempts to systematise the chemical elements. From the 1860s onwards, chemical properties could be described much more precisely using the — initially purely empirical — tools of valence and structural formulae. This confirmed the assumption that similar properties recur periodically with increasing atomic weight. In 1864/65, John Newlands was the first to develop a system of 65 elements in which the chemical properties recurred in every eighth position. In 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer independently developed the periodic table of the elements, which is still valid today. Mendelejev in particular pointed out elements that had not yet been discovered and were missing from the system, which were later actually found.

This provided practical chemistry with an extremely useful system which, in conjunction with a growing treasure trove of chemical measurement results and methods, enabled the development of many new substances and led to the establishment of an increasingly powerful industry, particularly in Germany. While the systemics did not yet say anything about the character of the chemical bonds and their physical background, it accelerated the further development of batteries using the new composites.

Dry batteries make small appliances mobile

In 1866, Georges Leclanché, who was in charge of telegraphy for the French railways and had become familiar with the problems of batteries at the time, invented a zinc-magnesium dioxide battery in Brussels, which soon became widely adopted due to its advantages. Leclanché later began to thicken the liquid electrolyte with starch in order to improve the handling of the batteries - which were used for doorbells, among other things. In 1886, the doctor Carl Gassner in Mainz succeeded in developing a truly dry battery by using gypsum as a binding agent and drastically reducing corrosion when not in use by adding zinc chloride, thus extending service life. Because a carbon rod was used as the core of the magnesium dioxide cathode to improve conductivity, the new dry battery was soon also called a zinc-carbon cell.

Sealed and easy to handle with a voltage of 1.5 volts, it became a worldwide success in several standardised sizes and is still being built today. One of the first applications was the torch. This was followed by all kinds of portable electrical and electronic devices that would have been unthinkable without it. In 2021, the global market for the non-rechargeable zinc-carbon battery totalled 9.2 billion US dollars and continues its slow growth.

In industrialised countries, however, the zinc-carbon battery has since been largely replaced by the alkaline manganese cell developed by Karl Kordesch at Union Carbide in the USA at the end of the 1950s. Alkaline batteries are much more demanding to manufacture, but have more than twice the energy density, a much lower internal resistance, half the self-discharge rate, a much lower risk of leakage, a better environmental footprint and cost only about half as much per charge. Introduced commercially at the end of the 1960s, they now have a worldwide turnover of 8.8 billion US dollars. Soon they are likely to replace zinc-carbon batteries in countries where the simpler production of this outdated technology is still more cost effective.

Eighty years after Carl Gassner, Karl Kordesch had a much more detailed knowledge of the electrochemical reactions involved in his design. This was because Joseph John Thomson's discovery of the electron as a charged elementary particle in 1897 had made it possible to formulate and explain them much better. Positively or negatively charged atoms or ions were created by the loss or gain of electrons (in Thomson's atomic model, electrons were embedded in an evenly distributed positively charged mass). Generalising the familiar oxidation and reduction reactions, all reactions in which electrons are exchanged have since been called redox reactions — including all electrochemical reactions in batteries. In the alkaline-manganese cell, which unlike the zinc-carbon battery requires a separator, several reactions are superimposed and must be carefully balanced. As far as one can tell from his 1960 patent, however, Kordesch's invention of the alkaline battery was not yet based on the material science findings resulting from quantum theory.

Classic rechargeable dry batteries fail to catch on

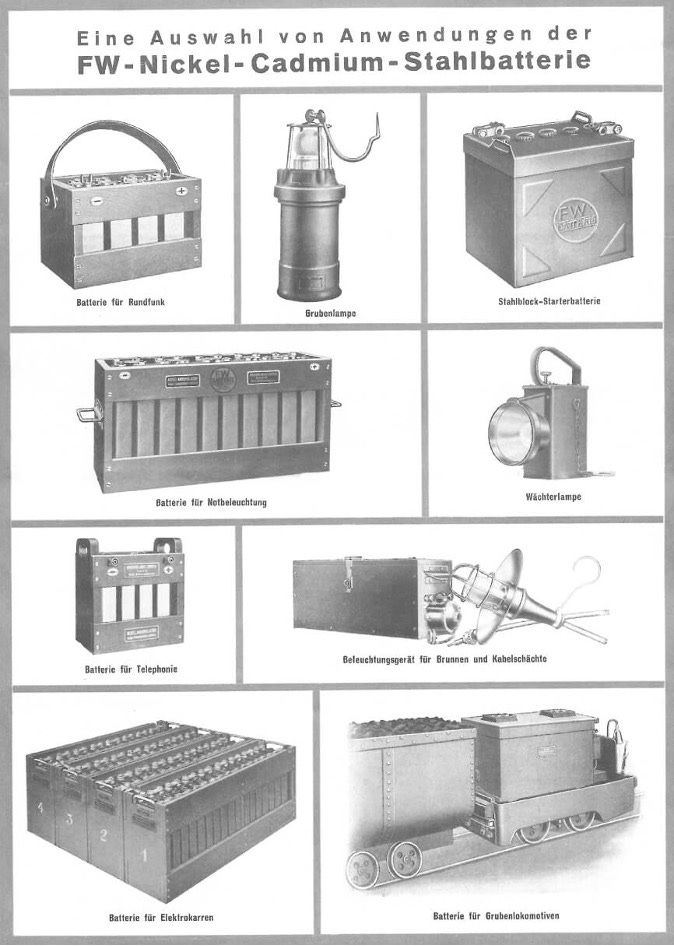

In the search for a rechargeable battery with a higher energy density than the lead-acid battery, Waldemar Jungner in Stockholm first invented a silver-cadmium battery and then, in 1899, the cheaper nickel-cadmium battery. Powered by a silver-cadmium battery, an electric car was able to travel 150 kilometres on a single charge as early as 1900. A long-running patent dispute with Edison later got Jungner into trouble. Although it had a significantly higher energy density, the nickel-cadmium battery (NiCd battery) could not prevail against the much cheaper lead-acid battery for starter batteries and larger storage requirements. And for powering road vehicles, the internal combustion engine had already achieved an almost unassailable position. However, NiCd batteries did play a role in weapons systems during the Second World War.

Initially, only open cells were used due to gas formation. In 1933, gas-tight NiCd cells with slightly different chemistry were developed, which were produced from the 1950s onwards in the standardised sizes used for dry batteries. However, at 1.2 volts, they had a 20% lower voltage than zinc-carbon batteries. Until the 1990s, these small rechargeable batteries became increasingly widespread as a replacement for non-rechargeable primary batteries, until they were largely banned due to the toxic cadmium - today, only large custom batteries of this type are still in use.

In 1967, the nickel-metal hydrid battery (NiMH battery) was then invented at Battelle in Geneva as a further development. It does without the toxic cadmium, has a higher energy density, is now also somewhat cheaper, but discharges itself more quickly and has a lower output. By now, it has largely replaced the NiCd battery in the consumer sector due to the EU ban. At the beginning of the new millennium the trend towards electro-mobility initially gave this low-maintenance battery a boost: in 2008, more than two million hybrid cars with NiMH batteries were built worldwide. For the most important applications, however, the lithium-ion battery is now far superior to the NiMH battery. In 2023, global NiMH sales totaled 2.4 billion dollars compared to 56.8 billion dollars for lithium-ion batteries.

In addition to the main battery types mentioned here, a whole range of other designs and chemical combinations have been tried and tested over the years, some of which have been used for niche applications. The topic of electricity storage has fascinated thousands of inventors, scientists, engineers and investors for two centuries as electrification has increased and ever smaller electrical devices have become widely used. However, the major breakthrough only occurred a few decades ago with the help of modern materials science. The next instalments of this series deal with this development.