Big was beautiful - How steam power shaped our institutions

History of technology - The discovery of nanoworlds enables a renewable energy supply for all / episode 12

Translation from the German original by Dr Wolfgang Hager

In episode 9 of this series, I announced that I would present four fundamental innovations for a sustainable energy supply that arose from the discovery of nanoworlds some one hundred years ago. In the last two episodes, we have seen how photovoltaics, against great odds, has challenged fundamental assumptions of the energy system. Before presenting power electronics and its significance for the entire electricity system in more detail as the next innovation, it is helpful to first look back and take a closer look at how the established electricity supply actually came into being. In doing so, we will discover that many assumptions and structures that are still largely taken for granted in the energy world and politics today were historically created based on preconditions that are no longer true today. This episode deals with the development up to the Second World War, while the next one will focus on the growing contradictions since the 1970s.

Classical power supply technology relies on large central power plants

The electricity system in most countries is still essentially based on classic electromechanical heavy current engineering:

Huge water or steam turbines drive electricity generators sharing the same drive shaft so evenly that the alternating current generated always has exactly the same frequency. The frequency — at whose rhythm the alternating current flows back and forth — must be synchronous throughout the entire grid, because major differences can cause serious disruptions. Imbalances between generation and consumption cause small divergences from the target frequency (in the European grid 50 hertz, i.e. 50 oscillations per second). These divergences are used to control generation so that it matches consumption at all times: the steam pressure at the turbine is regulated so that the correct frequency is restored. Large, heavy turbines are ideal for this purpose because their inertia allows them to compensate for small fluctuations in consumption.

After generation in the power plant, the electricity is transformed to high voltages for transport over longer distances using transformers as high as houses to limit the losses in the transmission lines. On the consumer side, the voltage is lowered again in several stages. If the voltage in a line drops too much due to high consumption, it must be corrected — if conventional technology is used — by mechanically switching the transformer connections. Because of the large effort involved, there are only a few measuring and switching points in traditional grids, which is compensated for by considerable reserves in the line capacity. By centrally controlling a manageable number of large power plants, large supply grids can be operated stably in accordance with this logic.

The development of this system has understandable historical roots and has strongly shaped our thinking, our institutions and our economic structures. Now, however, the increasing generation of electricity with hundreds of thousands of small solar and wind power plants is calling this logic into question. These do not obey fixed schedules and feed their electricity widely dispersed at the level of the distribution grids. In some transmission lines, the electricity even flows in the opposite direction at times. The simple pattern of top-down distribution is disrupted. A completely different approach to controlling the overall system becomes necessary. Perhaps decentralised power generation is a dead end? How and why did the current structures come about in the first place?

The discovery of electricity as a versatile, clean energy source

The principles and components of the electricity supply system that are still dominant today were already developed in the 19th century. It took until around 1930 for a corresponding supply system and the corresponding institutions to fully emerge in the most important industrialised countries.

When Alessandro Volta developed the first functioning battery in Pavia around 1800 with Volta's Stack, a continuous voltage source became available for electrical engineering research for the first time. In 1809, Humphry Davy developed the arc lamp in London, the first lamp capable of providing a continuous, bright electric light. In 1820, Hans Christian Oersted in Copenhagen discovered the magnetic effect of the electric current. Conversely, in 1831 Joseph Henry in New York and Michael Faraday in London discovered the generation of an electric current by a variable magnetic field. From 1832, Faraday researched electrolysis. With these elements, the basic principles of electrical engineering had been discovered, even though it was still not really understood how electricity and magnetism were connected.

The first practical applications soon followed. In 1834, Moritz Jacobi built the first functioning electric motor with direct current and used it to power a boat on the Neva in St. Petersburg. In 1854, Wilhelm Sinsteden invented the lead accumulator, which was later significantly improved by Gaston Planté. Building on various precursors, Werner Siemens, Charles Wheatstone and Samuel Varley finally developed the first industrially usable direct current generators independently of each other in 1866. For the first time, electrical energy was available in quantities that made widespread use possible.

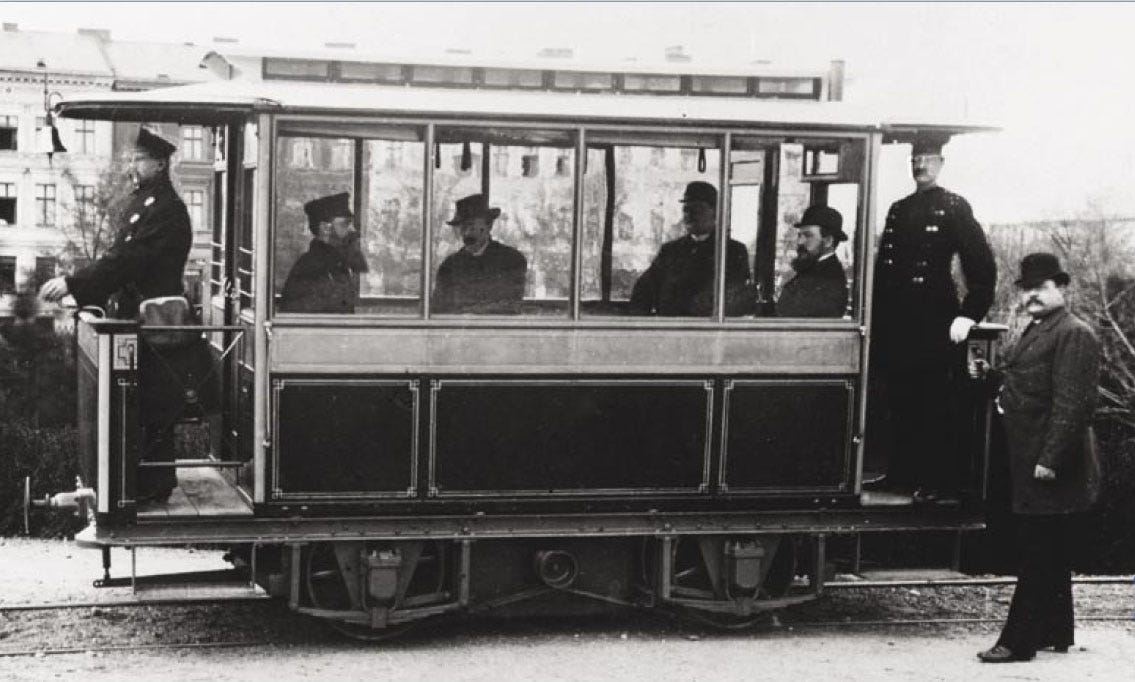

This gave rise to further inventions and industrial initiatives. From 1870, copper was produced by means of electrolysis. In 1879, Siemens put the first electric railway into operation in Berlin. That same year, Edison made the use of electricity attractive to a broad public with the invention of the carbon filament light bulb. From 1880, he began to set up small direct current distribution networks, first in the US, later in Europe as well. This subsequently gave rise to the company AEG in Germany and General Electric in the USA.

Edison was an extremely versatile inventor and entrepreneur who applied for over a thousand patents, not just in the field of electricity. His great merit, however, was not individual inventions but his thinking in terms of systems. He developed the vision of networked supply systems from electricity generation to the light bulb in the home and the engine in the factory. To achieve this, he had to organise the cooperation of a wide range of specialists as well as industrial and political actors.

Alternating current technology allows electricity to be transported over longer distances

Direct current was required for the first electric motors and for electrolysis. Therefore, in the first generators, the alternating voltage produced by the rotation had to be converted into direct voltage by automatic pole reversal with sliding contacts. But experiments with alternating voltage continued. As Oersted and Faraday had already shown, the transfer of energy between electric and magnetic fields only took place when the strength of the fields was changed - either by movement or by changing the current strength. This was the basis for the functioning of electric motors and generators.

In 1864, James Clerk Maxwell succeeded in formulating these relationships in a few differential equations that were barely comprehensible to laymen, thus establishing a comprehensive theory of electrodynamics which became the springboard for many further developments.

Due to transmission losses, the range of Edison's direct current grids was limited to a few kilometres. Since water power, which was sometimes more distant, was cheaper than steam engines to run generators, and since larger steam engines were cheaper to run than small ones, intensive efforts were made to seek to overcome this limitation.

In 1881, Gaulard and Gibbs patented a transformer in London that is essentially still being built today. They wound two coils around an iron core, which was ideal for concentrating magnetic fields. If alternating current was sent through one of the coils, a magnetic field built up with each oscillation, the energy of which could be tapped by a current flow in the other coil. If the number of turns in the second coil was greater than in the first, the voltage was correspondingly higher there than on the input side, but the electrical current was correspondingly lower. This also worked the other way round. With the same power (voltage times current), electrical energy could be "transformed" to a different voltage level.

In 1884, they impressively demonstrated that even large distances could be bridged by increasing the transmission voltage with alternating current, by transmitting electricity from a hydroelectric power plant 50 km away to an exhibition hall in Turin. While in Europe the Hungarian company Ganz & Compagnie spread the concept, in the USA the inventor and industrialist George Westinghouse was convinced of the advantages of alternating current (AC) networks and bought the American rights to the transformer patent in 1885. Only two years later, he had AC networks with 130,000 incandescent lamps in operation or under construction. The competition with the direct current networks of his competitor Edison, which took place mainly in the USA, lasted for many years. This was because the range of the direct current networks was limited, but electric motors could only be operated with direct current at that time.

Therefore, since the invention of the transformer, many inventors have tried to develop motors using alternating current. In a complex mix of parallel inventions, competition and mutual influence, several inventors contributed to the development of polyphase alternating current as well as the corresponding generators and motors: Galileo Ferraris (Turin), Nikola Tesla (New York), Friedrich August Haselwander (Offenburg), Charles S. Bradley and others. This was not least a formidable mathematical challenge.

The breakthrough came in 1888 with the concept of three-phase alternating current with corresponding motors and generators, which Mikhail von Dolivo-Dobrovolski developed at the AEG company in Berlin. In 1891, in collaboration with Charles E. Brown of Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon (later Brown Boveri & Cie), he demonstrated at the International Electrotechnical Exhibition in Frankfurt am Main that the complete system worked: Electricity of 50 volts with a frequency of 40 hertz was generated in a hydroelectric power station, transformed up to 15,000 volts, transmitted over 150 km to Frankfurt and transformed down there to drive one large and several smaller motors, as well as powering 1000 light bulbs. That won them over. On the other side of the Atlantic, Westinghouse triumphed with Tesla against Edison in the competition for the lighting of the 1893 Chicago World's Fair: the halls brightly lit with alternating current and the fluorescent lamps invented by Tesla ended the "Battle of Currents" to universal admiration.

With these inventions, all the basic technologies for today's global power supply system had been fully developed by the early 1890s.

The systemic change in technical energy use through the introduction of electricity

From the user's point of view, the arrival of electricity offered a variety of benefits. With electricity on tap, light, mechanical propulsion and heat could be generated in small and large quantities without any further effort for transport and storage - without exhaust fumes, dust and noise, and quite simply switched on and off. On the one hand, this meant greater comfort in private households and a growing market for electrical appliances. On the other hand, and this became increasingly important, involving a huge leap forward in development for skilled trades, industry and the service sector. Muscle power and central steam engines — from which mechanical energy had previously been transmitted to individual production machines via complex belt drives — could be replaced by electric motors of any size that performed work decentrally, directly at the workplace and easily controllable. This allowed the construction of completely new types of machines in which electrically generated heat could also be used in a targeted manner. Electricity thus opened up a huge potential for the decentralised use of technical energy on the user side. What had previously only been possible in manual labour or in large factories could in part be done in small businesses or at home. In addition, completely new possibilities also opened up for large-scale industry, e.g., electrochemistry.

From a systemic point of view, electricity was a new, intermediary energy carrier that introduced completely new flexibility and thus new technical possibilities to use energy — versatile, clean, easily transported and controlled.

Hydropower, which until then could only be used very locally as mechanical energy in the few places where it occurred, could suddenly be converted on a large scale with increasingly efficient turbines into versatile electricity that could be transported with low losses over hundreds of kilometres to where it was needed. Most of the electricity, however, had to be generated from fuels in thermal power plants.

The combustion process that previously took place in gas lamps, steam engines and furnaces was outsourced to the power plants by interposing electricity as an energy source. This not only had the advantage of making the final use of energy more flexible, small-scale and cleaner, but it also meant that fuel utilisation on the generation side could take place more efficiently in large power plants, and exhaust gases and ashes could be more effectively captured.

But the additional conversion steps also have their drawbacks. While electricity can be converted into mechanical energy and heat with high efficiencies, the greater part of the thermal energy is inevitably lost in the thermal power plant when heat is converted into electricity. Therefore, it did not and does not make sense to use electricity produced with coal, oil or gas to generate larger amounts of heat. Direct combustion at the point of use of the heat is — where technically feasible — much more efficient.

A crucial property of three-phase current is its extremely dynamic character: as such, it cannot be stored. Consumption and generation must always be exactly in balance. This requires a high degree of coordination and standardisation along the entire chain from generation through different voltage levels of the grids to final use, synchronously throughout the entire supply area. Alternating current cannot be stored in buffer storage facilities like wood, coal, oil or gas in order to compensate for fluctuations. Storage first requires conversion to other forms of energy. Edison's DC grids still sometimes relied on battery storage, which helped to compensate for irregularities and fluctuating utilisation of the transmission lines. But batteries remained expensive for a long time and the necessary conversion of alternating current into direct current was very costly for a long time (see next episode of this series).

A complex control system that would have optimally coordinated a large number of consumers and producers "in real time" was not conceivable with the technical means available at the time. Therefore, for a rough control of consumption, schedules of the industrial consumers were set, while for small consumers, empirical values were collected. Otherwise, the system was controlled from the production side: a few large power plants were operated with the limited means of communication in such a way that the grid frequency was kept constant as an indicator of the balance between production and consumption. In the process, for lack of better control options, it was accepted that large parts of the grid were hardly utilised during much of the time. In addition, considerable power reserves were held in reserve, especially in large water storage power plants, which could step in at short notice.

As we shall see, this requirement for synchronous, largely storage-less operation of the overall system and simplified top-down control by large power plants had considerable influence on the emerging structure of the electricity supply industry.

The different development of electricity systems up to the First World War

The differences in the evolution of electricity supply in the different industrialised countries clearly show that not only technologies but also different cultural, economic and political conditions influence the development of large socio-technical systems — and that, conversely, the development of technology has an influence on the formation of institutions.

In the USA, the construction of the large Niagara power plant in 1895 brought about rapid agreement on a "universal power system". Existing direct current grids were integrated via a mechanical coupling. As a compromise of diverse interests, a grid frequency of 60Hz was agreed upon. The consensus was facilitated by a generational change: Thomas Edison, who had quibbled with alternating current until the end, withdrew when his globally active company became the General Electric Group. Courses of study in electrical engineering had been established at many universities. A new generation of engineers grew up who could better cope with the complex concept of three-phase current. But Thomas Edison had been the key pioneer who initiated the transition from the development of individual devices to the design and realisation of entire systems. These required completely new forms of cooperation, from the most diverse disciplines and trades, from science, industry and politics. Even in Edison's time, this led to the building of international industrial empires and a close entanglement of industry and politics that had not previously existed.

In his comparison of developments in Chicago, London and Berlin, the American historian of technology Thomas P. Hughes (Hughes 1993) described in great detail how the different economic and political conditions in the three countries, which were most important for the electricity industry at the time shaped the development of distribution systems which differed significantly — despite sharing the same basic technology.

Having large industrial customers and large manufacturers of electrical equipment meant that larger grids could be developed quickly in Chicago and Berlin. This made it possible to use increasingly efficient power plants and, thanks to a diverse clientele, to make good use of the plants' capacity. In Chicago, which was a city dominated by large industrial companies, the self-confident electrical industry instrumentalised politics to achieve its goals — in some cases using questionable methods.

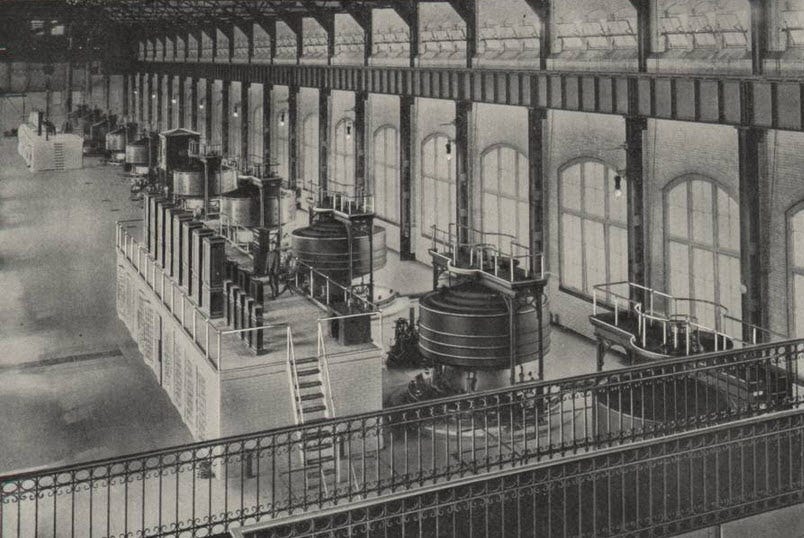

In the fast-growing city of Berlin, politicians who purposefully regulated to speed up development cooperated well with the newly emerging electrical companies. Politicians had already supported the introduction of the first direct current networks by Rathenau's Allgemeine Elektricitätsgesellschaft (AEG) with well-considered regulation. After the same AEG had decisively advanced the development of three-phase technology and had entered the field of power plant construction, all those involved quickly agreed on a universal system with 50 Hz. AEG and Siemens, who originally had different roles, became competitors but also worked together time and again in the interest of a common, standardised system.

In London, by contrast, characterised by a fragmented economy that had been equipped with steam engines much earlier, politics prevented the development of larger networks. In most of Britain, each community wanted its own individually designed systems. The electrical industry remained small-scale. As late as 1914, London, with its complex municipal structure, had at least ten different mains frequencies and an even higher number of mains voltages, which significantly hindered the development of a market for generators and electrical equipment.

Around 1911, the average capacity of power plants in Chicago was 37 megawatts, in Berlin 23 megawatts and in London 4.7 megawatts. The efficiency of the power plants in London was only about half of that in Berlin. In London, more than 60% of the electricity was used for lighting, in Chicago and Berlin only about 20%. Accordingly, the degree of utilisation of power plants in London was much lower.

The large companies in the electrical industry, which are still familiar today, grew at breathtaking pace: Westinghouse, General Electric, Siemens, AEG, BBC (BrownBoveri&Cie). Before the First World War, the German electrical industry was the world leader with about 50 % of world production.

The rapid development in Germany, combined with an increasingly aggressive nationalism and rearmament in the German Reich, led to growing concerns in England, which had experienced a rapid growth spurt at the start of the century in the wake of the first industrialisation. Per capita income and population grew faster in Germany than in England or France — in the USA, the growth rates were even higher.

Co-evolution of technology and institutions

In 1926, the economist Nikolai Kondratiev posited in his essay The Long Waves that technological innovations trigger cycles of economic development lasting 40 to 60 years, overlaid by shorter business cycles. According to this influential theory, a first cycle was triggered at the end of the 18th century by the steam engine and the mechanical loom, a second around 1850 by the railway and steel production, and Kondratiev saw a third just at its peak — triggered by electrotechnical and chemical technologies. (Parallel to the electrical industry, there has also been a rapid development of industrial chemistry, especially in the USA and Germany.) This technology-centred view — which also spoke of industrial revolutions in sometimes different ways of counting — lasted for a long time. It was linked to the idea of a continuous sequence of technological and subsequently social development stages. Especially after the Second World War catastrophe, such a view offered hope for a better future.

But this view could not explain the different developments in different countries. Therefore, from the 1960s onwards, economic historiography became increasingly interested in the social context of technical and industrial developments. It found that the cultural and institutional preconditions for what later became known as the "industrial revolution" had already been created in the late Middle Ages, and that the scientific and technical precursors had also been established much earlier than had long been assumed. Apparently, the cultural and institutional framework conditions had a greater influence on the development than had been assumed until then. The different development of electricity systems in different countries just described is an example.

This led to a new perspective on development since the Middle Ages. The economic historian Douglass C. North, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1993, spent many decades analysing the importance of institutions for economic development and thus for general development. North understood institutions very generally as "the rules of the game in a society". The essential characteristic of the new rules of the game, which have led to ever-faster technical and social changes since the 19th century, is today seen as the increasingly close connection between scientific knowledge and technical-industrial development.

Instead of industrial or even technical revolutions, we now prefer to speak of a New Economy. Douglas C. North contrasted the first economic revolution, in which property was introduced in the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agriculture, with the "second economic revolution", in which scientific knowledge and economic development are closely linked. In 1996, the historian Margaret C. Jacob showed in a comparative study how widely scientific knowledge from Copernicus to Newton was assimilated in England, even in the artisan milieu, and how it specifically shaped the development of the technical precursors of the steam engine. She found that from a cultural point of view, the industrial revolution was already complete by 1815. The (relatively) democratic patterns of interaction in English society played a decisive role in this — in contrast to France, where the absolutist form of government before the French Revolution largely prevented communication between engineers in the army and civilian endeavours.

This approach, which has been gaining ground since the 1970s, brings into focus the fact that already in the nineteenth century, "immaterial production" was gaining in importance over "material production": scientific knowledge, technical innovation, the development of a supportive institutional framework, and finally the development of software that can support all of this. Despite a long-running discussion about the service society and the importance of innovation, we are only slowly beginning to understand what this means. Especially as the material conditions of our lifestyle are brought back to our attention more clearly with the ecological crisis. The roles of matter, energy and information are shifting.

Remarkably, steam power and electricity have helped shape our state structures almost from the beginning of modern states. In 1830, at the time of the discovery of electromagnetic interaction, Europe was in a state of ferment. In France, the July Revolution drove out the last Bourbon king and established a bourgeois regime that continued the conquest of Algeria. The Poles revolted unsuccessfully against Russia, and many emigrants, including Chopin, found refuge in Paris. The Belgians pushed through the establishment of their own state against the Netherlands. Romanticism, which also emerged as a reaction to the onset of industrialisation, gained influence. In 1832, a cultural epoch came to an end with the death of Goethe. In 1837, Queen Victoria ascended the British throne. With increasingly aggressive colonialism, the great empires expanded.

Nicht zuletzt die Nutzung der Kohle hat die Welt im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts grundlegend verändert und zu einer massiven Machtverschiebung geführt. Noch 1780 waren alle Länder im Wesentlichen auf Brennholz und Muskelkraft angewiesen. Im Jahr 1900 wurde weltweit noch etwas mehr traditionelle Biomasse als Kohle verbraucht. Aber 97% der Kohle wurde in Europa und Nordamerika produziert, 34% in den USA und 29% in Großbritannien (Öl, Erdgas und Wasserkraft machten zusammen im Vergleich zur Kohle nur fünf Prozent aus). Das hatte wirtschaftliche Folgen: Zwischen 1820 und 1900 stieg der Anteil der USA an der weltweiten Wirtschaftsleistung von 2% auf 17% (Großbritannien 6%→9%, Deutschland 3%→8%).

It was not least the use of coal that fundamentally changed the world in the course of the 19th century and led to a massive shift in power. As late as 1780, all countries were essentially dependent on firewood and muscle power. In 1900, the world still consumed slightly more traditional biomass than coal. But 97% of coal was produced in Europe and North America, 34% in the US and 29% in the UK (oil, natural gas and hydropower together accounted for only five per cent compared to coal). This had economic consequences: Between 1820 and 1900, the US share of global economic output rose from 2% to 17% (Britain 6%→9%, Germany 3%→8%).

Underestimated until today: Hydro and thermal power plants forced centralisation

Since the 1890s, the principles and technologies on the electrical side of power supply systems have remained essentially the same until a few years ago — for a good hundred years.

But there were technical developments in the mechanical drive energy of the generators that had a significant impact on the development of electricity systems.

The first power plants were driven by steam engines. After larger distances could be covered with three-phase alternating current, the invention of efficient water turbines led to a relatively rapid development of hydroelectric power plants from 1890 onwards. Especially in California, in the Alps, in Scandinavia, in Japan. But where there were no mountains or large rivers, people remained dependent on thermal power plants.

The steam turbine soon prevailed over the steam engine, which was complex and vulnerable with its pistons and gears. Here, steam drives blades mounted on a rotating shaft, which can be connected directly to the generator without a gearbox. To this day, most of the world's electricity is produced with steam turbines. To do this, steam must first be generated with a heat source — whether by burning coal, oil or natural gas, by heating water in nuclear reactors, or by concentrating solar radiation with mirrors.

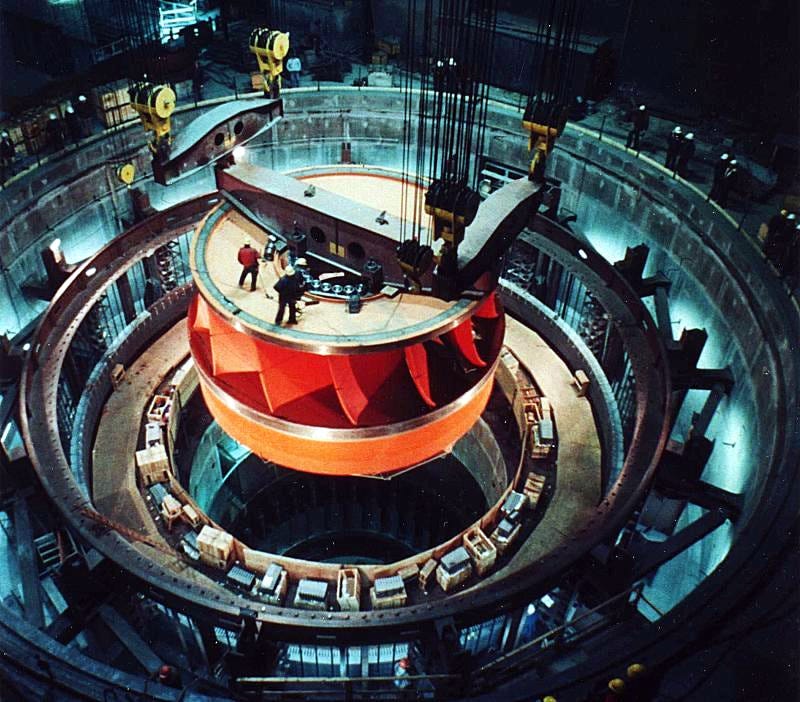

Considerable technical and institutional development thrust was caused by the fact that the efficiency of both hydro-power plants and thermal power plants increases with their size. This is due to physical reasons.

For hydro-power plants, the effect is that the resistance within the pipe to water flow decreases sharply with the diameter of the pipes. A doubling of the pipe diameter results in a decrease in resistance to 1/16th. (The braking effect of the pipe wall decreases with the distance from it. In turbulent flow, the effect is even stronger).

With electricity, that’s different: If you double the diameter of a solid copper cable, the electrical resistance for direct current only drops to a quarter (proportional to the cross-section). For alternating current, the resistance drops even less because the current can only flow on the conductor's surface due to the alternating magnetic fields (this is why cables made of thin strands are used for alternating current). At difference to mechanical and thermal systems, in electrical systems the size advantage is marginal and essentially due to mechanical components or heat effects.

In thermal power plants, there are several physical reasons why larger machines are more efficient than smaller ones. Basically, the efficiency of heat-power machines — i.e. the conversion of thermal energy into mechanical energy — is limited by the temperature difference involved. For very hot steam and water cooling, it is less than 50%. The fact that the surface area decreases in relation to the volume with larger units has multiple consequences for the efficiency: the heat losses due to radiation are lower; the flow resistance and friction losses are lower; the longer turbine blades can better absorb the energy of the steam; the more robust design allows higher steam pressures. To make the most of all this, sophisticated multi-stage turbines and novel materials had to be developed. Even with today's engineering, the efficiencies of steam turbines are highly dependent on size: 10 kW: 2%; 1 MW: 22%; 100 MW: 43%. Because of lower temperatures compared to coal-fired power plants, even large nuclear power plants with 1300 MW only manage 35%. From the 1970s onwards, the possibilities for increasing steam turbine output had been largely exhausted. Only gas turbines were able to further increase efficiencies to up to 60% thanks to higher temperatures.

The First World War prompts politics to push through even larger, more efficient structures

The relationship between institutions and technical-industrial development is complex. While the formerly dominant concept of stages of development has been abandoned, neither social nor technical development proceeds on a steady course. Disruptive events can suddenly render institutional barriers surmountable. For example, before the First World War, the growth of power plants and electricity grids was most advanced in Germany and the USA, but it could not fully realise its potential because of the large amounts of private capital required. This changed with the First World War: states intervened and imposed larger, more efficient structures to supply the defence industry.

During the First World War, it became impossible for Germany to continue importing saltpetre from South America, which led to bottlenecks not only in the production of fertilisers for agriculture, but also of explosives and ammunition for the armaments industry. As a result, the Reich government financed a huge ammonia factory in Piesteritz based on the Haber-Bosch process still used today, and a 180-megawatt lignite-fired power plant was built in just 9 months to supply it. With a 110kV transmission line to Berlin, the power plant became the starting point of a large-scale national power grid after the war.

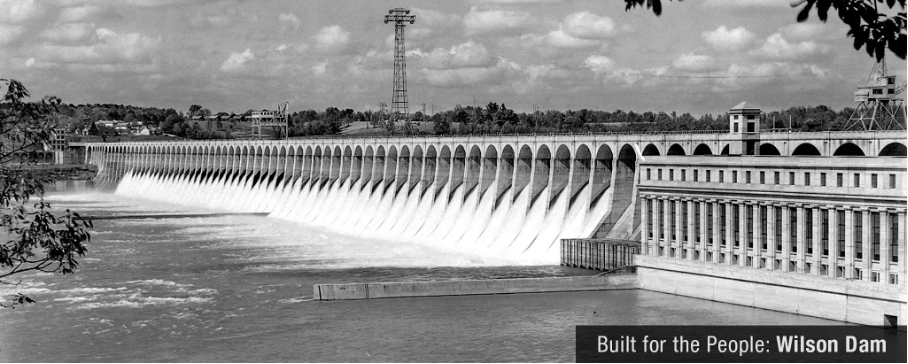

Similarly, to secure the nitrogen supply for wartime needs, the US government invested over 100 million dollars in an ammonia factory (using the cyanamide process) and a large fluvial power plant on the Tennessee (Wilson Dam). After the war, it was barely used at first. The visionary industrialist Henry Ford wanted to make it the starting point of a large electrification project, but this was rejected. It was not until 1933 that President Franklin Roosevelt took up Ford's idea of regional development through electrification with the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and made the power plant the starting point of the most ambitious project of his "New Deal". Only after several years of litigation did the federal TVA prevail against the stubborn resistance of the private power suppliers.

In England, the deficiencies of the 600 different electricity systems had become all too obvious during the war. The Electricity Supply Act of 1919 was the start of standardisation and centralisation: Four regional Joint Electricity Authorities largely took over the large power stations, and in 1926 the Central Electricity Board was founded, which by 1938 had built the National Grid, England's first synchronised transmission network. In 1947, the British electricity supply was completely nationalised.

In France, too, small, private electricity companies dominated until the First World War and developed relatively slowly. While annual electricity consumption in the USA was 121 kWh per capita in 1913, it was only 30 in France. The loss of two-thirds of coal production at the beginning of the war led to increased attention to the benefits of electricity, a vigorous expansion of hydroelectric power in complementary climatic zones and the construction of a network of transmission lines. The state provided loans, coordinated planning and mandated cooperation of private undertakings. The capacity of the hydropower plants was doubled within five years. From 1910 to 1938, the share of hydropower in electricity production rose from 30% to 55%. Driven by a new generation of managers, many of whom came from the civil service, the small utilities grew into ever larger regional suppliers in the interwar period. The increasingly large power plants and transmission lines were often built with state participation. The growing state influence then led logically to the nationalisation of almost the entire electricity industry under the umbrella of EdF in 1945.

Thus, since the beginnings of electricity use, i.e. for almost two hundred years, technology and social institutions have grown in mutual influence: scientific knowledge, technical infrastructures, private companies, the legal framework, state energy policy, industrial and private electricity use. The co-evolution of technology and institutions, again and again, led to different results in different countries. But, at the same time, the international flow of knowledge grew increasingly intensive, so that the scientific and technical fundamentals remained similar everywhere.

In the next installment, we will see how the large monopolistic electricity suppliers were able to maintain their hold for a long time after the Second World War. From the 1970s onwards, they increasingly fell into a crisis of legitimacy. However, the liberalisation of the electricity markets at the turn of the millennium and the subsequent restructuring of the supply industry were only the beginning of a transformation process in which new technologies fundamentally question the control and growth logic of the electricity system that had evolved over almost two hundred years. In view of the close linkage between the development logics of the electricity system and our industrial societies outlined in this instalment, it is not surprising that changes — as compelling as they may be from a technical, economic and ecological point of view — meet with massive resistance from those who have prospered with the previous system. Not only financial interests, political influence and sheer convenience are at stake — long-established organisational structures, ownership, decision-making mechanisms and thought patterns that have accompanied our democratic governance structures since their emergence are being called into question.