50 years of restructuring the electricity system - From central control to network cooperation

History of technology - The discovery of nanoworlds enables a renewable energy supply for all / episode 13

Translation from the German original by Dr Wolfgang Hager

The previous episode of this series dealt with the long history of developing the electricity system up to the Second World War. It showed how strongly thermal and hydroelectric power plants, with their propensity for ever larger units, shaped our institutions. Things initially continued this way in the reconstruction years after 1945, with nuclear energy also fitting into the old pattern. But from the 1970s onwards, the technical, economic and social conditions for the power sector began to change. First, heat-power co-generation broke up the old monopoly structures and led to the liberalisation of the electricity markets. Then the increasingly rapid rise in the share of "system-inappropriate" decentralised and volatile generation of electricity with wind power and photovoltaics began to put the system under pressure. It has so far been able to cope with a contradictory patchwork of additional rules and new grid technologies. The forces of inertia of the old system are trying to save the centralist control logic. This only delays the necessary change. A new control logic is inevitable...

Article series on the history of technology:

The discovery of nanoworlds enables a renewable

energy supply for allThe episodes so far:

Nuclear fission: early, seductive fruit of a scientific revolution

Where sensory experience fails: New methods allow the discovery

of nano-worldsSilicon-based virtual worlds: nanosciences revolutionise information technology

Climate science reveals: collective threat requires disruptive overhaul of the energy system

The history of fossil energy, the basis of industrialisation

The climate crisis is challenging the industrial civilisation: what options do we have?

Nanoscience has made electricity directly from sunlight unbeatably cheap

Photovoltaics: Increasing cost efficiency through dematerialisation

Continuity after the Second World War

The Second World War brought no fundamental changes in power systems — except expansions for the armament industries and considerable destruction.

As we saw in the second episode of this series, efforts began in the late 1940s to harness the energy of the atomic bombs, that had just been developed, for civilian purposes. For this aim, the heat from nuclear reactors was converted into electricity with turbines and generators. The repeated consideration of using the surplus heat for industrial or heating purposes failed, because nuclear power plants had to be as large as possible for reasons of efficiency (up to three times as large as conventional coal-fired power plants), and could not be built in densely populated areas for reasons of safety.

Compared to fossil-fuel-based thermal power plants, two characteristics of nuclear plants led to a further centralisation of power systems: firstly, their size and secondly, the need to operate them at a relatively constant output. The reduced ability to adjust their output is mainly due to the fact that temperature changes result in material fatigue. In nuclear plants, this is to be avoided as far as possible because of the safety risks and the time and cost involved in maintenance work on radioactively contaminated parts of the plant. In addition, because of the low cost of fuel, and high capital costs, the plants must be run at high capacity. In the end, the risk of failure of the large units and their inflexibility could only be countered with larger interconnected systems. Other than that, nuclear power did not fundamentally change the electricity system. In any case, its initial contribution was still very small: in 1973 it accounted for only 0.76% of the world's primary energy. By 1978 - when the nuclear meltdown in Harrisburg caused new orders for power plants to stop - its share had risen to 2,7%.

Initially, the areas of application for electricity also remained largely unchanged. Petroleum products still dominated the rapidly growing road transport. The electrification of the railways made slow progress. Steam locomotives were often replaced by diesel locomotives. Coal still dominated heat generation for buildings and industry. In space heating, individual stoves were increasingly replaced by central heating. Then oil gained ground as a fuel. Coal-derived town gas had long since been replaced by electricity for lighting, but held on where relatively clean and small-scale heat generation was important: in the kitchen, in industry and crafts, for hot water. Natural gas (see episode 8) only slowly appeared from the 1950s in the USA and from the 1960s in Europe. Compared to directly burning fossil fuels, electricity was still too expensive to use for heat generation, because in most countries it was mainly produced — with unavoidable conversion losses of about two-thirds — in thermal power plants from the very same fossil fuels.

In the USA — according to the American historian of technology Richard F. Hirsh — an "electricity consensus" emerged in the first decade of the twentieth century between the electric utilities and politicians. This consensus viewed the electric utilities as natural monopolies to be left alone for the most part by the State regulatory commissions as long as they could satisfy the growing demand for electricity with ever lower tariffs. Thanks to progressively larger power plants and more efficient technology, the electricity providers generally were able to meet these expectations until the 1970s.

In Germany, a system similar to that in the USA had existed since the beginning of the century with large regional suppliers, each serving a monopoly area. The north-south line of RWE built beginning in 1920, which provided an ideal way of balancing hydroelectric power plants in the Alps and coal-fired power plants in the Ruhr area, received international attention. However, below this level, smaller municipal facilities and industry-owned power plants still had an important role to play. With the Energy Industry Act of 1936, the National Socialists codified this structure - to avoid large power plants making Germany more vulnerable militarily. The law remained in force largely unchanged until 1998.

In France, the state-owned EdF had a fully planned monopoly based on uniform principles. In the post-war years, the main focus was on building large dams. Pressed by the CEA (Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique), which is also responsible for the development of atomic bombs, EdF then got involved with nuclear energy. Today, nuclear power accounts for 70% of electricity generation, more than in any other country. In the beginning, the easily regulated dam power plants were an ideal supplement to the continuous generation in the nuclear power plants, later electric night storage heating was used to compensate (today 14% of space heating is electric).

In other countries, too, the structure of electricity supply remained largely stable until the early 1970s — although my account here is essentially limited to the Western industrialised countries. Large monopolies, benevolently supervised by the state, supplied growing areas with proven technology.

From the seventies: legitimacy crisis of the electricity monopolies

At the beginning of the 1970s, however, the technical, social and political conditions changed. Student unrest and strikes in the large industries had begun to shake the social consensus of the post-war reconstruction years. The nature conservation movement, the Club of Rome, the first United Nations Conference on the Environment and the anti-nuclear movement increasingly raised the question of whether this kind of growth could carry on indefinitely.

In the USA, according to the technology historian Hirsh, the "electricity consensus" entered a crisis of legitimacy because technical efficiency could no longer be further increased. Larger power plants created new problems. All this was then compounded by the energy crisis of 1973, which led to a drastic increase in the price of fossil fuels (see episode 8 of this series). This suddenly led to rising electricity prices and public criticism of both the electricity system and the wasteful use of electricity, for which the electricity companies were not entirely blameless. The legitimacy crisis of the electricity monopolies was part of a more fundamental legitimacy crisis of the industrial growth model and the dominance of the industrialised countries. Greatly alarmed by the energy crisis, Democratic President Jimmy Carter, after long negotiations, pushed a comprehensive legislative package through Congress in 1978 that was supposed to bring about a more economical use of energy and an increased use of national resources.

There had been increasing calls from experts in the environmental movement and academics for new planning methods such as least cost planning (LCP), integrated resource management (IRM) and demand side management (DSM). "Energy Strategy: The Road not Taken" was the title of a legendary essay by Amory Lovins in Foreign Affairs in 1976. The regulatory commissions in the US States, which had always been responsible for regulating the electricity industry, became more active and a new consensus on system management in which utilities and regulators cooperated more closely seemed to be possible for a while.

But, in the early 1980s (see episode 10), as the energy crisis eased and cheap fracking gas became available, greater reliance on market forces and deregulation of electricity markets began under President Reagan. The development in the different states was and is not uniform.

In Western Europe, there was a similar development. In Germany, the Netherlands, Scandinavia and Italy in particular, a growing environmental and anti-nuclear movement asked similar questions. It also provided significant impulses for applied research. Particularly from the countries where the movement was strong, many well-founded proposals and scenarios for a sustainable energy policy continue to be produced to this day.

In Western Europe, there was a similar development. In Germany, the Netherlands, Scandinavia and Italy in particular, a growing environmental and anti-nuclear movement asked similar questions. It also provided significant impulses for applied research. Particularly from the countries where the movement was strong, many well-founded proposals and scenarios for a sustainable energy policy continue to be produced to this day.

Despite quite different starting situations and interests in the countries of Europe, the European Union increasingly gained influence over the electricity systems of the member countries. Although energy policy has played a central role in the European unification process since the early days of the EU with the Coal and Steel Community and EURATOM, responsibility for energy policy lies primarily with the member countries.

In Eastern Europe, energy shortages intensified into a veritable energy crisis in the 1980s. Since the 1970s, the Soviet Union had increasing difficulties in meeting the growing energy demand of the energy-poor member countries of COMECON, which it had been satisfying with subsidised supplies since the beginning of the 1960s, thus strengthening the cohesion of the bloc. The financing of joint gas pipelines became increasingly problematic. In 1969, Kossygin took up again an older idea for a common Comecon electricity system. In 1976, the Comecon Council adopted a plan that envisaged a wide-ranging 750kV high-voltage grid and a number of new power plants — not just nuclear ones as originally envisaged. The realisation of the electricity plan was also considerably delayed (with the Chernobyl accident in 1986 playing only a minor role). Declining energy supplies from the Soviet Union contributed significantly to the economic decline, increasing disintegration and finally the collapse of Comecon in 1991.

How cogeneration broke the monopolies

Largely unnoticed, but highly consequential was a provision in President Carter's Energy Bill that allowed independent power producers to sell electricity to the monopoly companies. It was retained in the subsequent liberalisation spurts, with different arrangements in the States. The starting point for the new competitors were the huge, unused quantities of waste heat in the power plants.

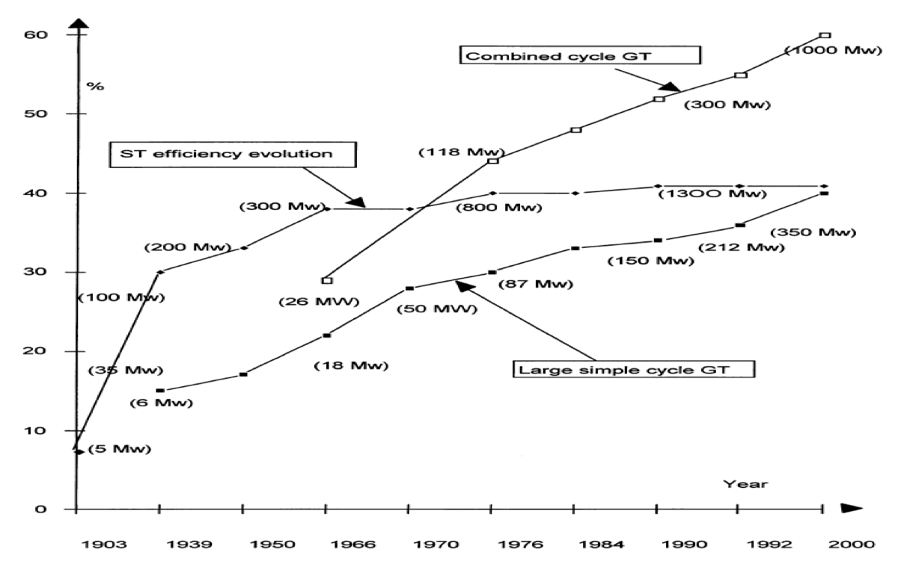

It turned out that small cogeneration plants, which primarily provided heat for industry, were also able to supply cheaper electricity than the conventional large power plants, especially since the advent of efficient small gas turbines. This is because they made use of both the electricity and the waste heat that was uselessly released into the environment by large power plants. Natural gas was cheaply available in increasing quantities, it burned relatively cleanly and could directly drive turbines at higher temperatures than the steam from coal-fired boilers. The same companies that had developed jet propulsion for aircraft after the war used their knowledge to develop gas turbines. The first wind power plants, which were still quite inefficient, also started to attract interest. This undermined the monopoly position of the old players.

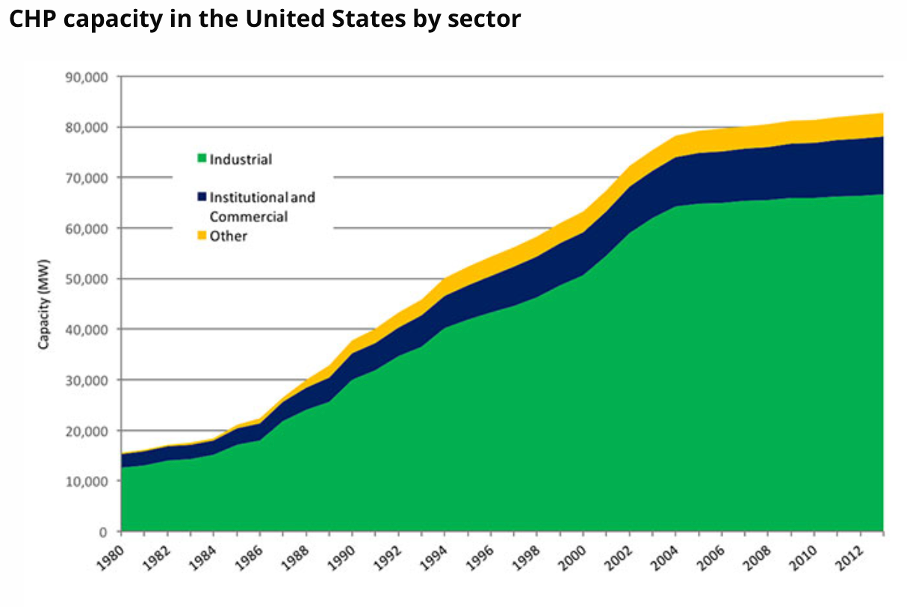

The use of waste heat from power plants is basically an ancient technology. Edison already supplied hot steam from his first electricity plant in New York. However, this became difficult with the emergence of large-scale power plants. Even in the “co-generation boom” that began after 1980, heat in the USA was mainly used for industrial purposes and not for space heating. This was different in Europe.

The key pioneer in the development of combined heat and power (CHP) was Denmark. Especially in Northern Europe, district heating systems using heat from CHP plants had been built since the 1930s. However, their share in electricity production remained low. With the oil crisis and the environmental movement's criticism of the inefficient use of fossil fuels, interest in combined use increased and new technologies were developed. Building on the experience with district heating systems, nationwide heat planning was introduced in Denmark after the oil crisis. It systematically connected large CHP plants in major conurbations to district heating networks. In a second phase, from the mid-1980s onwards, local heating networks were built in less densely populated areas, which were supplied by the smaller CHP plants that had been developed in the meantime: compact, mass-produced small power plants with gas turbines. The frequently cooperative organisation of the local heating networks led to an optimal operational management: in order to enable a cost-saving reduction of the return temperature, members made sure that the thermal insulation of the buildings was improved. The district heating costs vary depending on location; on average, they are far below the district heating costs in Germany. Only in a third phase did cogeneration take on a role in industrial process heating — Denmark has few energy-intensive industrial enterprises. By 1999, more than 50% of electricity production in Denmark derived from cogeneration. A decisive factor in this development was close government regulation, which was continuously improved. After the oil crisis, it was initially aimed at avoiding dependence on oil and gas imports — after a few years it was possible to cover demand with the country's own oil and gas production. Then, in the 1980s, the effort to avoid climate-damaging emissions became the predominant concern. Increasingly then — much earlier than elsewhere — biomass, solar thermal energy and wind power were used for heat generation, facilitated by large heat storage facilities.

In the Netherlands, which has its own gas reserves, the emergence of new technologies for cogeneration also played a decisive role in breaking up the monopoly structure of the electricity industry. Initially, gas turbine technologies were increasingly adopted by traditional electricity producers. From the seventies onwards, industry began to use CHP plants for in-house use. Then, as the legal framework changed from the late eighties onwards, the electricity distributors started to cooperate with the industry and to compete with the traditional power plant monopolies. They were the real agents of change in the Netherlands from 1989 onwards, breaking up the old supply structure. In 2007, CHP accounted for almost 30% of electricity generation.

Germany has for a long time operated CHP plants both industrial and in urban district heating networks, but their share of total electricity generation remained low for a long time. With the emergence of new CHP technologies, they attracted greater interest. From the nineties onwards, there was increasing debate about combined heat and power plants and district heating. There was public funding from 2000 onwards. At about 12% in 2007, the CHP share in Germany was above the international average of about 9%, but well below the figures for Denmark, Russia, Scandinavia — and about the same as in China.

In France, which relied on nuclear power, and in individualistic Great Britain, district heating played no role and cogeneration only a minor one.

Only after the turn of the millennium, when the Danes had already started to replace fossil CHP with biomass CHP, solar thermal and wind power, did the EU and the International Energy Agency start to promote CHP with natural gas as a contribution to reducing CO2 emissions.

The emergence of CHP and small, independent power producers had a disruptive effect on the organisational structure of the electricity industry. Competition became possible. People experimented with electricity markets. It became clear that different roles had to be defined in these markets. The old monopolies in the electricity industry had to rethink their strategies. Technical innovation became a competitive advantage. But this all happened slowly at first. For the control logic of the electricity grids, CHP was not yet a big challenge, because they could be committed to timetables and reliably scheduled. The control and balancing function of the large power plants was not yet called into question, especially since improved communication technologies simplified the central administration of schedules.

Since the eighties: wind power foreshadows entirely new requirements

As early as in the 1980s and 1990s, however, when the liberalisation of the electricity markets was being considered, it became foreseeable that another power generation technology would soon pose much greater challenges to control technology: wind power, for it could not be obliged to adhere to timetables.

Wind power has been used since ancient times, especially for milling and pumping. Wind-driven power plants long remained economically and technically inferior to hydroelectric and steam power plants. But by the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, they were widely used in remote farms, especially in North and South America, until electricity grids were built in rural regions as well, or diesel generators became available.

Since the oil crisis, interest in this energy source had been revived, and attempts were made to build more efficient plants. Here, too, size was an advantage (see also episode 12) — but the output of wind turbines is still only about one-hundredth of that of thermal power plants. In 1978, the first modern wind power plant with a capacity of 1MW went into operation in Denmark. From 1991 onwards, electricity fed into the grid from wind power in Germany was remunerated at fixed rates. In 1995, only 0.15% of electricity generation in the EU came from wind power (USA 0.09%). In 2000, it was already 0.81% (USA: 0.15%, world: 0.21%). And for the first time, wind power plants no longer had to be operated at a constant rotational speed in order to comply with the grid frequency, but were able to make much better use of the wind's energy thanks to electronic converters (see next episode in this series) that allowed rotation at variable speeds.

It was not until the beginning of our millennium that wind power made its presence felt in the control logic of the grids - with thousands of turbines feeding difficult-to-predict amounts of electricity into the lower voltage levels of the grids: in 2010, wind energy supplied 20% of electricity production in Denmark (EU: 4.7%, DK 2022: 55%). But by then the institutional framework was already quite a step further.

Liberalisation of the electricity markets in Europe — the beginning of the restructuring of markets and grids

Starting in the 1990s, Europe has created the world's largest liberalised electricity market. Technology — the increase in gas turbines, cogeneration and the first wind turbines — and politics — the growing environmental movement on the left and the increasingly influential neoliberalism on the right — led to a situation in Europe, very similar to that in the USA, where the monopoly of the large power plant operators became increasingly untenable in the 1980s. In the meantime, the Western European electricity markets had become increasingly interconnected through the increasing cross-border trade in electricity. Moreover, with the opening of the Iron Curtain in 1989, the integration of Central and Eastern European countries into the European single market was on the horizon. From the end of the nineties, this led to a gradual liberalisation of the European electricity markets and the introduction of national and European regulatory authorities.

The concrete implementation of the new EU rules for the electricity markets is in the hands of the member states, allowing for considerable variations in practice. In principle, the monopoly for electricity production was abolished, but it was retained for the grids at the various voltage levels.

Even though the liberalisation of the electricity markets in Europe offered alternative electricity suppliers and independent electricity traders new opportunities, it was essentially geared to the established structure of conventional electricity supply. And the electricity supply companies, which have grown over a century, resisted and continue to resist threats to their dominance with every means at their disposal. The breakthrough of wind energy and photovoltaics therefore did not come as a result of deregulation, but with state-guaranteed feed-in tariffs for small, innovative electricity producers, which actually runs counter to liberalised electricity trading and centrally controlled top-down distribution.

In 2000, the share of wind and solar energy in electricity production in today's EU was still low at 0.8% (Germany: 1.6%, France: 0.0%) and could easily be managed with conventional technology. In 2022, however, wind and solar power accounted for 60% in Denmark, 33% in Spain, 32% in the Netherlands and Germany, and 29% in the UK. In the EU as a whole it was 22%, in France 17%.

Only a few years ago, the collapse of the systems was predicted if the share of fluctuating renewables would exceed 10 percent. In fact, coping with high shares of fluctuating feed-in in a market and a grid that were actually meant for controllable large-scale power plants, continued central control and top-down distribution, could only be achieved with a variety of additional rules, balancing markets, ex-post corrections, a lot of new technology, a lot of digital effort and a lot of frustration.

On the technical side, considerable effort was required for the digital control of the grid, which we will discuss in more detail in the next episode. After a hundred years or so, it became inevitable to gradually supplement the old, electromechanical technology geared to simple distribution flows. However, we are still far from replacing it and from really using the potential of the new technologies. The market mechanisms and administrative follow-up controls also remain essentially the same. But with the integration of millions of photovoltaic systems, wind turbines, EV charging stations and heat pumps, the complexity to be managed administratively has increased massively, while the centrally controllable large-scale power plants have been taken out of the market. Therefore, the control capacities on the lower and middle grid levels are being stepped up. This also results in a reallocation of responsibilities, which does not pass with out conflicts between companies and institutions at all levels. As moderator of a national distribution grid dialogue in Germany, I have had direct experience of just how intense tensions can become during this transformation process.

The new regulatory authorities, the politicians and the public, but also the technicians in the utilities are only beginning to learn how greatly the new energy sources are challenging the legacy structures. The whole electricity system is under a state of reconstruction, while still having to function reliably every second and relentless power struggles are raging behind the scenes.

Inconsistencies in an outdated market regime

An increasingly serious problem of the current market organisation is that it largely ignores the spatial dimension. To allow liberalised electricity trading while grids are still organised in monopolies, electricity is traded on electricity exchanges within spatially delimited "bidding zones" (market areas) according to uniform rules, quite independently of the concrete line capacities. Within a bidding zone, the wholesale price is the identical everywhere. It is as if all points in the area were connected by a copper plate. Grid bottlenecks only become relevant in the European electricity market when trading between the bidding zones, and there they do lead to significant price differences. Only after trading has been concluded do the transmission system operators — the players at the highest voltage level — intervene, if necessary, in the generation schedules, to match trading results to line capacities (redispatch).

Initially, such administrative interventions were rarely necessary, because the old monopoly companies had their power plants and grids well coordinated. Since then, however — due to the difficult-to-manage juxtaposition of market signals from the electricity exchanges, support measures for the expansion of renewables and the regulation of monopolistic grid expansion by the supervisory authorities — the geographical patterns of generation, consumption and grid capacities have diverged. Therefore, redispatch results in ever higher additional costs, which are passed on to all users.

The number of bidding zones varies greatly in the EU member states: Germany has only one, Sweden four, Italy five. If Germany were divided into two market areas, electricity prices in the industry-rich south would be much higher than in the north, where more solar and wind energy has been added — due to considerable transmission bottlenecks. The political debate about this is growing more heated. The occasionally significant price differences between the European bidding zones are an indicator of transmission bottlenecks — Norwegian consumers were not at all happy about the price increase after the recent opening of a new large transmission line to Germany. In the US and elsewhere, there are market models that provide better geographic control through geographically differentiated prices. In several US states, for example, electricity prices are calculated for several hundred grid nodes.

Simply removing all transmission bottlenecks in order to recreate the "copper plate" — the massive grid expansion often called for — and continuing to regulate everything from the centre is, however, an unnecessarily expensive solution. Incentives are needed again to ensure that electricity is generated close to consumption at exactly the right time — otherwise grid costs will continue to grow. As we will see, a variety of approaches to this have been developed and tried out in recent years: local electricity exchanges, concepts for "cellular energy systems", greater responsibility given to local grid operators, permission to supply neighbours directly. All concepts that are actually "anti-system" and introduce here and there elements of a decentralised "bottom-up" control logic into the system…

Another symptom of the contradictions of the current system are the endless delays and squabbles in the introduction of smart electricity meters in many countries: the issue is not really technical difficulties, but the hot question of who has access to which data, and who — if anyone — gets the right to control private consumption from the outside.

A fundamental challenge for the market system introduced with the liberalisation of the electricity market and refined since then are the completely different cost and time structures of the old versus the new power plants. The clearest example of this is the difference in construction times: Planning and building a factory for solar modules takes 2 years, for large solar power plants one year, for rooftop systems a few months. And with each factory completed, prices plummet. This is beyond the comprehension of the representatives of the old system. The planning mechanisms developed over decades had to allow decades for building large-scale power plants.

More serious is the different cost structure: wind and solar power plants have no fuel costs. The marginal cost of electricity generation is zero: the plants cost the same whether they generate electricity or not. In this they resemble the grids. Moreover, solar and wind generation is dependent on natural cycles and the weather. To compensate, additional flexibilities must be mobilised in consumption, in generation and with storage. Not only the short-term balancing of very different types of generation, but especially the long-term allocation of investments is becoming increasingly difficult under the current market mechanisms, because the future evolution of the risk profile is difficult to estimate. Thus, attempts are being made to improve the situation with parallel markets and special regulations — often without an idea where the journey should really lead…

Almost everyone is now committed to changing the electricity system - but how fast and where?

Thus, a simple, centrally controlled system has turned into a patchwork of complicated rules and contradictory logics. Quite a few people are nostalgic for the old days — out of convenience, or because they are threatened with losing their sinecures. To ensure competition and security of supply at the same time, the EU market rules list more than 70 different “market roles” in the complex web of electricity markets — and yet in many countries a few big players still dominate the scene.

These inconsistencies are an expression of a profound process of change in the electricity system, which on the one hand concerns institutional issues (market design, regulation, corporate structure, control logic, role of prosumers) and on the other hand the technical infrastructure, in which new technologies (if they are actually adopted) open up entirely new flexibilities and control logics. Both dimensions are closely linked.

Very different kinds of actors are introducing new regulatory approaches, trading platforms, monitoring systems, communication models, storage facilities, energy converters and flexible consumers into the system — with very different methods of management and control. Despite all the contradictions, they have contributed to both dimensions — the institutional and the technical — so that the system has not collapsed even with a high share of "system-inconsistent" electricity generation.

That a change in the electricity system is inevitable is now widely recognised. Even by most companies. But how fast? And in which direction? The social debate, in which different interests clash, revolves primarily around four sets of questions:

The need to reduce CO2 emissions to zero is now socially and politically accepted and perceived as increasingly urgent. But opinions differ on the pace to be set.

The growing competitiveness of renewable energies can no longer be doubted — even if they are disadvantaged in various ways by a variety of regulations, market rules and subsidies. But which sources and players should receive priority when trying to clear the regulatory undergrowth? Photovoltaics on all rooftops? Huge offshore wind farms? Hydrogen from solar power plants in sunny countries? Small prosumers? Neighbourhoods? Municipalities? or large corporations?

The new technical possibilities for converting energy, controlling energy flows and making consumption more flexible are breaking up compartmentalised markets and facilitating the advance of renewables. How well do the old dominant players manage to slow down the process? How quickly do they manage to develop business models that allow them to retain central control despite all the flexibility? How quickly do other companies and small suppliers manage to use the new technologies to bring the efficiency advantages of local markets and network-style control logics to bear?

High energy prices are handicap in international competition. Which industrial sectors, which countries can afford to be among the laggards in the great upheaval so as not to give up some of their privileges? Whereas at the turn of the millennium a handful of large corporations in Europe, America and Japan were still able to dictate technological development, new players, notably China, are now spoiling the traditional game. There is serious competition. Not just for individual products, but for systems. What kind of energy system do we want? Who should be calling the shots in this system?

The importance of these disputes should not be underestimated. The electricity system is becoming the core of the total future energy system. It is no longer just a matter of supplying traditional electricity customers: heat supply and transport must also be largely electrified, or coupled with the electricity system. With millions of electric vehicles and building system drawing electricity from, and feeding it into, the grid, both the number of flexibly acting system participants and the volume of electricity production are set to explode.

A fundamental controversy about the logic of control and the governance of our increasingly powerful socio-technical systems

The disputes about the control logic and thus about the might of the different players in the electricity system are continuing and will increase in intensity — so far largely misunderstood by the public. The question of control logic concerns both the institutional and the technical dimension.

As I try to show in the course of this series, new technical developments are creating completely new possibilities: Photovoltaics (see episode 12), which are becoming economically and technically dominant for physical reasons, allow for increasingly decentralised and cheaper sustainable power generation. Intelligent electronic management systems (see the coming episode 14) and new types of storage (episode 15) drastically increase the flexibility of the system and allow for increasingly decentralised and cheaper sustainable power generation. Finally, new techniques for converting electricity into radiation (episode 16) will enable unheard-of energy and material savings. This has consequences in all areas of life.

In order to avoid the loss of control, the legacy power utilities are trying to maintain the traditional central control logic, despite a massive increase in the number of plants to be controlled, by using new possibilities for central processing huge amounts of data. Therefore, at the very same time as new initiatives are developing local power exchanges and cellular systems for allowing interaction between autonomous local actors, other institutions are seeking to upgrade centralised control systems: They work on centralised access to the control of private facilities, on business models based on smart meter data, or a digital twin of the European electricity grids, which is supposed to provide a central overview. The public is hardly aware of these different concepts. There is simply a demand for more "digitalisation".

The debate resulting from the development of the power grid is of a fundamental nature. For it is increasingly no longer just about the traditional electricity system, but about the energy system as a whole, about sovereignty over data and the control of processes in all areas of life. China, for example, is pushing ahead with the integration of a wide variety of social and technical monitoring systems into AI-supported "city brains" that are supposed to allow "one screen social governance" and later be interconnected to form "nation brains" and beyond. City brains are not only being installed in China, but also exported along the new Silk Road to other major Asian and African cities. They are based on a clearly centralised vision of control, which Europe should counter not only with solutions offered by Western manufacturers for smart city systems, but also with an explicitly different governance logic.

The centralist control logic that has resulted from the history of our electricity systems ought to be quite explicitly questioned in democratic societies against the background of new technical developments. From my point of view, autonomous control of local systems that react to price signals is definitely preferable to grid operators' encroachment on all kinds of production facilities and heating systems — no matter how weakened and nuanced these approaches are currently presented. For there is more at stake. It is about the control logic of our society, which is increasingly dependent on technology, about self-determination and democracy.

The technical possibilities for using infrastructure to enforce decision-making mechanisms and control logics have grown by orders of magnitude. But the physical and technical reasons for centralisation that were paramount in conventional thermal and hydraulic energy production no longer apply in the new energy world. We are being freed from constraints that have been with us and shaped our thinking for two hundred years. Decentralised control is now becoming a genuine option.

So, firstly, we are faced with the task of managing the transition of the electricity system away from fossil fuels and towards renewables fast enough to largely avoid a climate catastrophe from which our children and grandchildren would suffer severely.

Secondly, we are faced with the challenge of choosing the new control logic of the energy system in such a way that self-determination and democracy are strengthened and not restricted by an increasingly centralised, high-tech control infrastructure. Authoritarian solutions would certainly fit into the logic of the development of the traditional electricity system. But with the different technical logic of nanoscience and the turn away from fire (see episode 9), we have a huge opportunity.

The fact that the new technical developments now offer a path towards a sustainable, decentralised, self-determined energy supply, which would also be economically superior, should have become clear by the end of this series.