The climate crisis is challenging the industrial civilisation: what options do we have?

Episode 9 of the series: History of Technology - Discovering the nano-worlds enables renewable energy supply for all

Translation from the German original by Dr Wolfgang Hager

This series explores the wide-ranging consequences of the scientific revolutions which impacted the technologies of both supply and use of energy, and which began at the turn of the last century. It involved a profound change in the way science sees the world and opened the door to previously unknown nanoworlds, worlds on the scale of atoms. The first episodes of this series dealt with nuclear energy, an early product of this upheaval, and then turned to newer developments that open up superior options to address the climate crisis. This episode reviews our progress so far and looks ahead to the remainder of this series.

The last two posts on climate science and the history of fossil fuels were rather long and depressing. These are topics that can make you lose sleep and make you doubt the future of humanity. The coming episodes will feature more pleasant developments.

Will we find the strength to overcome the climate crisis?

Our series on the history of energy technology started with the mysteries of electricity and various types of radiation, which led to the advance of science into the world of atoms and molecules and then soon to the discovery of nuclear fission with quantum theory at the beginning of the last century. The next stages were the atomic bomb, the rise and crisis of atomic power generation, and new methods of measurement enabling science and technology to advance further and further into the nano-world. Then, as a further success of nanosciences, came the almost unbelievable history of microelectronics, which, with information technology, produced a cross-sectional technology that has fundamentally reshaped our entire civilisation ever since. Information also plays a central role in the subsequent upheavals in biology, which revolutionised medicine but had only minor impacts on energy technology. Finally, we have seen in the last two episodes how the new nanosciences have exposed the fact that the energetic basis of industrialisation, the burning of fossil deposits from geological prehistory, disturbs the heat balance of our earth so drastically that the earth is threatening to become more and more uninhabitable. And how great the challenge is to choose a different path in time.

We find it so difficult as a society and individuals to deal with this situation that some are succumbing to resignation. "That our societies will still find their way out of their situation in time is wishful thinking." Jens Beckert, Director at the prestigious Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, recently stated at the conclusion of an article in the leading German weekly newspaper Die Zeit. I find such a definitive statement irresponsible and dangerous - his actual argumentation was more nuanced. Resignation will be joined by other dead-end responses: fear, anger, confrontation and activism, calls for the strong man, false promises and profiteering are on the rise in the face of the ever more clearly perceived existential crisis... We need to reach a common understanding about alternatives.

Dimensions of the challenge - misunderstood technology

The interrelated difficulties are described with ever-increasing intensity from different perspectives. We can perhaps break them down into the following points:

We are facing four a novel problem dimension:

The consequences of today's actions will only affect future generations. The climate damage we have already brought about by past actions is only slowly becoming more apparent. Even a change of course would take some time to take effect.

The challenges are global. Local contributions to solutions are important, but cannot provide a solution on their own. Communication, innovation and supply chains are globally interconnected - our perceptions and policies are ill-prepared for this.

Global injustice. Those who have historically contributed least to today's climate and environmental problems suffer the most and have the least resources to develop less harmful infrastructures.

Structures that have been built over time stand in the way of change:

Powerful economic interests defend old structures, technologies, subsidy networks that have grown over decades. They sow uncertainty, doubt and disinformation.

Complex and slow-moving economic-political-legal structures were developed for the old technologies and can only be changed with great political effort. They hinder urgently needed decisions, delay their implementation and inhibit learning processes.

We are trapped in an irresponsible consumer culture. We act as if our current level of material consumption is a basic human right that the policy makers have to guarantee. And as if our OECD standard were possible to achieve for 8 billion people.

The new sciences and technologies are largely misunderstood

The disturbing scientific predictions are difficult to comprehend because they are based on complex model calculations, as well as on findings and processes that contradict our everyday experience.

Everyday technology is no longer understood. Most people have given up trying to even begin to understand the nanoscience-based technologies on which they are becoming increasingly dependent. This leads to a feeling of fundamental insecurity.

Lack of technical understanding of the energy policy alternatives creates insecurity, leads to mistrust, to clinging to familiar structures, or even to a nostalgic desire to return to approaches that have already failed.

The second group of difficulties concern the social dimensions of the problem. These can be broken down further. There are intensive discussions about this, and that is important because it is in the social debate that decisions about our future will be made. As the perception of the problem grows, the sharpness of the dispute will increase.

This series deals primarily with the third group of difficulties, which I think is shamefully underestimated - the lack of understanding of the technical-scientific dimension of the problem and its possible solutions. For the preconditions for the familiar, more or less well-functioning negotiation processes between interest groups are less and less valid. Without understanding the new conditions, the climate crisis cannot be solved.

Humanity has used the enormous technical possibilities of the new sciences in largely conventional structures without really realising that the use of nanotechnological tools fundamentally changes our role in nature.

If we want to have a democratic choice about the use of these possibilities, we have to make huge efforts to ensure that the majority also understands what is at stake. We as a society must be able to properly assess both the dangers of the current path and the alternatives that are opening up with the new technologies. Without a concrete vision of the future we want, we will not have the strength to make the necessary changes. Having hesitated for too long, substantial efforts and a rapid break with old habits are necessary.

There is no turning back

We have eaten from the tree of knowledge, but have not yet quite grasped what we have let ourselves in for.

With the onset of industrialisation, wood became scarce in Europe by the mid-eighteenth century. Then, industry and population continued to grow faster and faster: from 1800 to 1850, the population in France increased by 25%, in Germany by 87%, in the United Kingdom by 153%. Wood was no longer sufficient and was increasingly replaced by coal. In the previous episode we showed how the use of fossil fuels evolved. The world's population rose from 985 million in 1800 to 1.65 billion in 1900 to 7.91 billion in 2021 - and 83% of primary energy consumed still comes from fossil sources. Global spending on oil and gas, which accounts for 65% of primary energy consumption, amounts to 5 trillion euros annually, about 5 per cent of global value added.

Fifty years of climate warnings have achieved little: Now we are at the point where we must not only prepare ourselves for serious delayed consequences of the emissions of the last decades, but above all, risk ever more profound and irreversible tilt effects of the climate system if we burn an amount of just ten times the current annual consumption. We have to put our technical-industrial civilisation, which has enabled humanity to grow eightfold in two hundred years through the use of fossil fuels, on a new trajectory in the shortest possible time.

What energies do we need?

The use of fire is considered to be a crucial element in the making of mankind. For thousands of years, people mainly used fuels to produce tools and ever more complex technical equipment. Water and wind power played only a marginal role. The transition from biomass to fossil fuels has not changed this, both technically and in terms of the perception of fuels and fire as the central source of energy. Now that fossil fuels are no longer an option, it is important to consider what we actually need as useful energy:

Heat. For heating, cooking and materials processing in industry

Light. For seeing, for communicating, for plants, for photochemical processes

Mechanical energy. For transport and materials processing

Electricity. For communication, information processing, controls

Chemical energy. As food and for chemical reactions (neither of which should be considered here as an energy source)

Light is the visible section of a much broader spectrum of electromagnetic radiation, ranging from radio waves to infrared radiation (heat radiation), visible light and X-rays to radioactive gamma rays. More than these five forms of energy exist only in atomic nuclei.

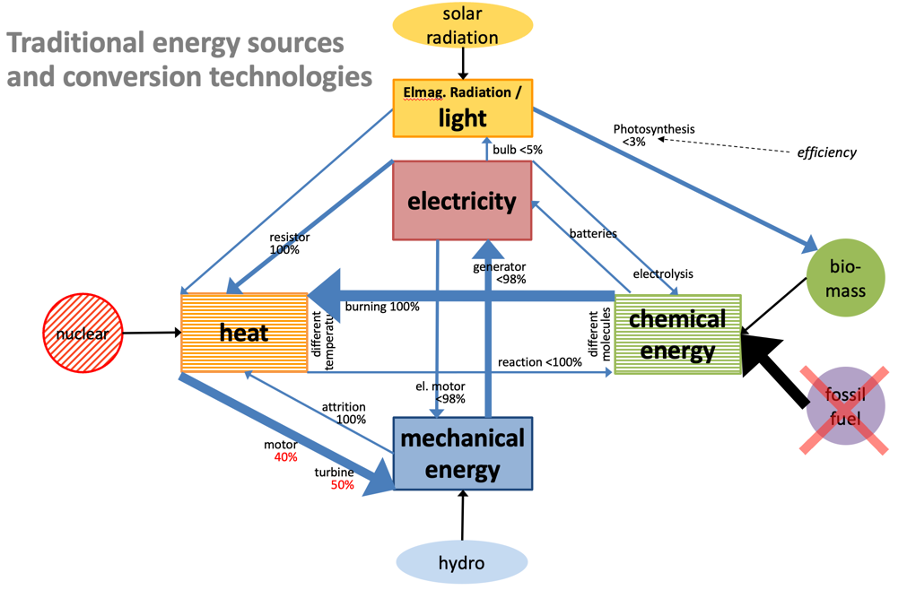

The decisive factors for energy supply are the technologies and the efficiency with which they can deliver useful energy from the sources available. This sometimes requires multiple conversion steps between different forms of energy. For example, electricity was largely generated from mechanical energy, which in turn is produced from heat, which is generated by burning the chemical energy of fuels: Three conversion steps using different technologies. Each of these involve losses. In addition, it is often important to consider which forms of energy can be easily stored and transported. Fuels, unlike electricity, can usually be stored easily. The energy sources and the conversion techniques of the classic energy supply are shown in the following diagram:

Electricity and mechanical energy are high-value forms of energy that can be converted into each other or into heat with efficiencies close to 100 per cent. The value of heat, i.e. the conversion efficiency from heat to other forms of energy, depends on temperature. Gas turbines can only convert up to 60%, lignite-fired power plants up to 45% of their heat input into mechanical energy. A whole branch of classical macroscopic physics - Thermodynamics - deals with the relationship between thermal energy (heat) and mechanical energy. It was established by Nicolas Carnot who published the results of his studies on the efficiency of steam engines (Réflexions sur la puissance motrice du feu et sur les machines propres à développer cette puissance) in 1824.

In 1980, the world still looked very different

Nuclear energy was a first attempt to use the new nanosciences to develop alternative energy sources. We saw in the first episodes of this series how it failed. After the Three Miles Island / Harrisburg meltdown in 1979, safety measures became so expensive that development stalled.

In 1980, when the failure of nuclear energy became increasingly apparent, the climate problem still looked different. If it had been possible, as credibly suggested at the time, to stabilise global fossil energy consumption with energy saving technologies and renewable energies, today’s outlook would be brighter. We would have had the time to slowly reduce fossil fuel use to zero as late as between 2040 and 2080 and still stay within the carbon budget for the 1.5-degree target (which was not yet known precisely at that time - see episode 8).

In the seminal study "Energiewende" published in 1980, the Freiburg Oeko-Institut presented a detailed scenario for the Federal Republic of Germany, in which fossil energy consumption would be reduced from 1980 to one-third by 2030. With this approach, they calculated, the fossil fuel needs of even a doubled world population living at the then comfortable living standard of West Germany could be met by the fossil world consumption levels of 1980.

Renewables were still struggling at that time, but already used seriously, especially as solar thermal energy. Hydropower had been developed to maturity, but was not available everywhere. Bioenergy was overestimated. President Carter had proposed a major programme for renewables and efficient energy use during his election campaign. Compared to today, they were still at an early stage, but they could have been used intensively and developed much faster. The oil companies started to invest in photovoltaics. But things turned out differently. In January 1981, Ronald Reagan, a friend of the oil industry, moved into the White House…

Fascinated by the new possibilities of digitalisation in communication, deluded by real falling energy prices thanks to new techniques in oil and gas production, lulled by misinformation from the fossil lobbies and therefore full of doubts about misunderstood alternatives, humanity has wasted a lot of time. Now time is running out to say farewell to fossil energies. So short that the costs in money and social terms of transforming the energy system have risen dramatically. Costly plants will have to be written off before their intended lifetime.Whole industries will have to be restructured and relocated in a short time. Workers and consumers, companies and public authorities have to adapt more quickly than they would like. A great deal has to be learned and invested in a short time.

Confused when faced with this situation, more and more clueless people are now proposing to try nuclear power again - perhaps not so clunky, and modular and scalable to fit contemporary tastes. It could be so simple - replace fossil fuel with nuclear fuel, diesel with e-fuels. A turbine could remain a turbine and a combustion engine remain a combustion engine. Nostalgia, longing for times when everything was simpler. Of course, old buddies with close professional ties to the nuclear power industry or younger ones attracted by the thrill of the potentially explosive nuclear fire, propose projects that give old concepts a new design. They also gladly collect the millions in funding that rattled politicians or those interested in the military implications are willing to dispense. Investors, too, are counting on eventually being able to make money with public subsidies. Countering this illusion, which costs us time and money that we no longer have, was the initial motivation for this series.

The idea of doing without fuel unsettles many people. They do not trust the idea of relying entirely on renewable energies, especially on sun and wind. This is quite understandable, because they do not yet grasp the new logic; and today's prosperity was created with the old one.

In the second half of this series, the aim is to help us understand how the scientific advance into the nanoworlds has by now produced a series of new technologies that, in combination, actually make it possible to put humanity's energy supply on a different, sustainable basis within a short time.

Four fundamental innovations make it possible to turn away from fire as the basis of technical civilisation

The lobbying campaigns of the fossil industries and their friends have long obscured the fact that the increasingly broad access to the nanoworld not only allows us to replace individual technologies. It has progressed to such an extent that a general overhaul of the entire energy system is not only necessary, but possible. And this overhaul has multiple benefits, quite apart from the climate problem which lends this turnaround its existential urgency.

It is therefore useful to look not only at individual technologies for solutions, but to consider the system as a whole. In the context of a new logic is increasingly apparent how the properties of individual components can complement each other. Past inventions take on a new meaning. In the last twenty years, experimentation with subsystems has brought many new insights. Different development strategies have become mutually supportive, old techniques have been dusted off and put to use in novel ways. Synergies have been discovered that enable much greater savings than originally assumed. This changes our perspective. While the emerging sustainable energy system builds on the achievements of the industrial system, it fundamentally renews its foundations.

In the next episodes of this series, we will describe four fundamental innovations that, together, can make a sustainable energy supply possible:

Photovoltaics. This allows electricity to be generated directly from sunlight. Without the wasteful detours via chemical energy, heat and mechanical energy.

Power electronics. With this, electric current can be converted almost without losses and digitally controlled. This revolutionises the generation, transport and use of electrical energy.

New types of batteries. This allows electrical power to be stored and transported much more cost-effectively, efficiently, and with less space and weight than before.

LEDs and lasers. Direct conversion of electric current into light. This makes lighting and material processing much more efficient. Additive manufacturing (3D printing) enables great savings of material and energy.

After presenting these fields of innovation, we take a look at the system as a whole. And this is perhaps the most difficult to grasp, because old certainties no longer apply. The brief descriptions already make the direction of development clear: electricity, which was at the very beginning of the revolution in the physical world view of last century, moves right to the centre. Heat is generated from electricity, not the other way round. As I will explain, this brings considerable efficiency gains in the overall system. To speak of a farewell to fire does not seem exaggerated. Oxidation processes will still play a role in material processing and electro-chemistry - but they have had their day as a source of heat that drives everything.

And all this is not just a distant vision. The technologies exist, some of them familiar and some of them re-evaluated in the new context. As I will show: Times and costs make a rapid transition possible if we move forward decisively.

Technology competence

This means that we can not waste any more time and money. For this, timely prioritisation of technologies is important. To this end, some criteria will be developed at the end of this series: Which detours could have been avoided? How can we recognise development potentials? What do we need in the overall context of the new energy system? Can this be transferred to specific areas, such as transport?

And finally, the question of who needs to learn what if we are to meet the challenges. On the one hand, it is about qualifications and skilled workers at all levels who have to manage the rapid transformation. On the other hand, it is about the competence of everyone, worldwide, to grasp the meaning and consequences of this upheaval in their respective roles as consumers, workers and citizens. This also means understanding, at least to some extent, the historical and technical dimensions of this turning point. Role models, priorities, habits, business models and power structures will have to change - everywhere. Those who learn faster will have an advantage. And the change in primary energy sources will shift the scales internationally.