Photovoltaics: Increasing cost efficiency through dematerialisation

Episode 11 of the Series: History of Technology - The Discovery of Nanoworlds unlocks Renewable Energy Supplies for All

Translation from the German original by Dr Wolfgang Hager

We are facing the imperative to replace fossil fuels as the basis of our industrial civilisation in just a few years. This requires a profound transformation of our energy systems. This series shows how the revolution in the natural sciences at the beginning of the last century was instrumental in making this possible. Nuclear energy was an early attempt to use the advance into the nanoworlds for energy supply. As we have shown, it failed utterly.

The topic of the last episode was the inexorable rise of photovoltaics, despite much resistance and the fact that it involves a different system logic. In this episode, we first want to explore three questions: What are the deeper reasons for the disruptive reduction of costs, energy and material consumption of photovoltaics? Can this development continue? How do other energy sources compare? To answer these, it is necessary to look a little more closely at the underlying technical principles.

The cost reduction was not only due to economies of scale – nanotechnological innovations were decisive

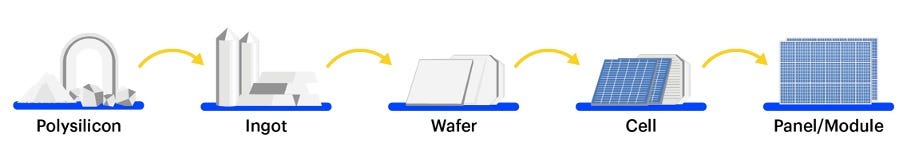

More than 95% of production is still based on crystalline silicon, the basic technology on which the first solar cell with any appreciable efficiency was based in 1954. In the succeeding seven decades, this technology has been improved at every stage of production. Step by step, energy, material and labour have been saved at every stage of production, while ever more sophisticated technologies have increased the conversion efficiency of solar radiation into electricity. To understand these cost reductions - and the future development potential - we need to distinguish between the different stages of the manufacturing process:

First, metallurgical silicon with a purity of about 98% is obtained from quartz sands in an energy-intensive smelting process. Only a small part of this is produced for photovoltaics. Most of it goes to the metal industry (aluminium and steel), as well as to the electronics industry, which uses similar processes to the solar industry.

Then the silicon is converted into a gaseous compound and processed into high-purity polysilicon in another very energy-intensive process - mostly in the continuously improved so-called Siemens process, which was developed in the 1950s to meet the stringent requirements of the semiconductor industry. Because of the high temperatures required, the production of polysilicon is very energy-intensive and takes place in large plants. Since 2011, energy consumption has been halved. Nevertheless, the production of polysilicon consumes 44% of the energy needed to manufacture a photovoltaic module.

Thermal losses can best be avoided in large plants. This is why polysilicon production is concentrated in a few plants worldwide, which also have longer construction times than the factories of the subsequent production stages. Currently, it is the bottleneck of the entire supply chain, which led to increased module prices in 2022. However, due to expanded production capacities, prices are already falling again.

After this, 20 cm thick and several metres long, flawless round crystal rods are drawn from the molten polysilicon at a well over 1400 degrees (Czochralski process) - so-called mono-crystalline ingots. To minimize crystal defects, the silicon must first reach a purity of 99.999999%. Until just a few years ago, multi-crystalline ingots, which are cast from less pure material, were the dominant method. This process requires much less energy, but the resulting so-called multi-crystalline solar cells are much less efficient, so they have now been largely replaced by mono-crystalline cells. To produce wafers in the next step, the ultra-hard ingots are sawn into thin slices less than 1/5 millimetre thick using diamond-tipped wires. Since 2010, the silicon requirement per watt of PV output has been reduced by 68%. The reduction in energy and material consumption up to this point in the supply chain is only partly due to the optimisation and scaling of classic technologies. Achieving high purity levels and ever larger, nearly defect-free mono-crystalline silicon wafers, first used in microelectronics, required extensive and ongoing nano-science developments. Larger wafers and less wastage have contributed significantly to cost reduction. In addition, the reduction in wafer thickness has to do with nano-science advances in the next stage of production. The steps up to this point now account for about 28% of module costs.

The subsequent processing of the wafers into solar cells is the most technologically demanding step, which has seen the most advances in the last decades. This is where the actual 0.2 mm thin power plants are created. The physical details of power generation at semiconductor interfaces, which are not easy to understand, allow for many variants with different layers and methods of contacting. Rapidly successive generations of fabs or the replacement of some machines in existing production lines have increased the efficiency of commercially available silicon cells from about 16% in 2010 to about 24% today. This has contributed significantly to cost reduction, as less module area is needed for the same output. In addition, it has been possible to increase the service life, which is now forty years for good modules (but is not fully taken into account in electricity cost calculations because it is assumed that they will be replaced by better modules in commercial installations before then).

Since the production of solar cells from wafers is complex with a whole series of sequential processing steps, this stage accounts for about half the equipment costs of the entire value chain. Parallel production lines with cross-connections and shared infrastructure allow high flexibility and machine utilisation in large factories. Overall, however, the cost of moving from wafer to cell only accounts for about 22% of the total cost of a solar module, because little additional material is needed.

This is quite different for the final step, in which the cells are electrically connected and encapsulated under a glass cover to form air- and watertight modules. A lot of material needs to be handled here: The solar cells from the previous production stage account for less than 10% of the weight and about half of the cost of the finished modules. For this reason, module production is often carried out separately from cell production, close to the end users. Despite increasing automation, this stage still accounts for 46% of the human labour in the entire supply chain. To ensure that a PV panel lasts 30 to 40 years and makes the best possible use of solar radiation, high-quality materials and meticulous work are necessary. Special glasses, plastic films, casting resins, frame constructions and electrical connection techniques have been developed for this purpose. Commercial modules today have an efficiency of up to 22% .

Unlike conventional large-scale power plants, photovoltaic cells and modules can be mass produced in large quantities. New integrated factories have capacities of between 10 and 20 GWp per year, or 25 to 50 million modules. Economies of scale arise especially in the highly complex cell production. Moreover, the corresponding production facilities - except for polysilicon - can be installed within less than two years. The planning and construction time for photovoltaic power plants is also less than two years. This results in innovation cycles that are ten times shorter than for fossil or nuclear large-scale power plants and even significantly shorter than for wind energy.

When considered over the entire supply chain, the decisive innovations that led to the unprecedented cost reduction of photovoltaics in energy technology were not of a classical but of a nano-technological nature. The increase in the efficiency of the conversion of solar radiation into electricity plays a prominent role. The increase in module efficiency from 14 to 22 percent between 2010 and 2021 made it possible to reduce the module area required for a given power output, and thus the corresponding costs, by 36%. Since about three quarters of the power plant costs are directly dependent on the module area, this has a major impact on the resulting generating costs, even though the modules themselves now only account for less than half of the costs.

Other nanotechnology-related cost savings include lower wastage in wafer production, material savings due to thinner cells, better low-light behaviour, lower temperature sensitivity and longer service life. Overall, it can be estimated that a good half of the cost reduction of PV modules since 2010 can be attributed to nano-technological innovations. and not - as is often claimed - primarily to the learning effects of mass production of large quantities.

Since the 1970s, semiconductors not made of silicon, which do not require elaborate large crystals but can be deposited in thin layers using a variety of processes, have continued to promise significant advantages. In 2009, they accounted for 17 per cent of the market. CdTe (cadmium telluride) and CIGS (copper indium gallium selenide) stood out in particular. Today, CdTe accounts for a market share of only four per cent. Especially the different CIGS or CIS variants have not been able to meet the high expectations so far, because efficiency and service life have always lagged a little behind the development of silicon cells.

The cost reduction of photovoltaics continues - persistently falling material requirements

Ten years ago, only insiders would have believed that photovoltaics, and silicon technology in particular, would continue to develop at such a sustained rate. This raises the question: can this continue? Classical methods of reducing the costs of material goods through mass production and improved processes reach their limits after a while, because at some point the material and energy input can only be significantly reduced through differently designed products.

The unprecedented cost reduction in microelectronics became possible because the product is computing power, which could be produced with less and less material effort: The actual active unit, the transistor, could be made smaller and smaller through nano scientific findings - its volume shrank in three dimensions. At the same time, the switching frequency could be increased more than a thousandfold. The result is an unprecedentedly rapid and still ongoing reduction in the material and energy required for information processing.

The solar cell, on the other hand, does not process information (which can be extremely condensed thanks to microelectronics), but the natural solar radiation striking a surface - a finite amount of energy. Attempts to concentrate this incoming radiation with mirrors and lenses have in turn proved to be material-intensive and costly. The output of solar cells is therefore limited by their material surface. The cost reductions have come from, on the one hand, lower costs per area, and on the other, ever-increasing efficiency in the conversion of solar radiation into electrical energy. Slowly, however, it is becoming more and more difficult to reduce the area costs of the solar modules commonly used today and to increase the proportion of solar radiation that can be converted into electrical energy with silicon technology.

Two developments in particular, however, have the potential to significantly reduce the cost of photovoltaically generated electricity once again, and to further change the structure of electricity supply. The first path is additional and significant increases in efficiency with other cell concepts and semiconductor materials - i.e. nano-technological innovations. The second way is to reduce the substantial costs of safely enclosing the sensitive silicon cells in rigid glass housings - this now accounts for half of the module costs.

Special cells have long been developed and produced for use in space. They offer significantly higher efficiencies, but are too expensive for terrestrial mass applications. By now, it is possible to produce cells in the laboratory that can convert up to 47% of sunlight into electricity - and that is not the theoretical end of the story. To achieve this, several light-sensitive semiconductor boundary layers are arranged on top of each other. These layers can use different sections of the solar radiation spectrum - silicon can only absorb a limited portion of this spectrum. Such multi-junction cells require the juxtaposition of up to twenty different layers.

For some years now, however, intensive experiments have been going on with a promising new class of materials, the perovskites, which are expected to lead to significantly lower costs. These are flat crystals made from combinations of commonly occurring elements whose photovoltaic properties can be varied to cover different parts of the solar spectrum. By now, researchers have learned to produce the thinnest perovskite layers inexpensively using simple methods, while at the same time significantly improving their efficiency and lifespan. As an additional layer on silicon cells or as a combination of several different perovskite layers, they promise cheaper, more efficient and - depending on the design - even less vulnerable solar cells. The first commercial production facilities are under construction. In the laboratory, efficiencies of 32.5 percent were achieved for silicon-perovskite tandem cells, and 27.4 percent for perovskite-perovskite tandem cells. Lifetimes of 30 years are now within reach. (In order to reduce the required module area again as much as between 2010 and 2021, it would be necessary to increase the module efficiency to 34.5%). The production facilities will be less complicated than for silicon cells. A factory with a capacity of only 100 MWp should be able to produce modules that yield electricity production costs of 3 to 4 ct/kWh in Spain and recoup the energy required for production in as little as half a year.

The second approach to significantly further reduce costs is to lower the high cost of the mechanical structures supporting the actual solar cells (glass surfaces, foils and frames of the modules, mounting systems, racks), and which account for more than 90% of the total weight. This can be achieved by integrating the solar cells into the structural elements of buildings of all kinds that are anyway needed. This is called Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) or Vehicle Integrated Photovoltaics (VIPV). There are two ways to achieve this.

On the one hand, adapted glass modules can be used directly as the outer skin for all kinds of buildings - as elements of façades and roofs, noise barriers, vehicle surfaces, road surfaces. In that case, the structural costs are incurred only once. An alternative is to apply solar coatings to well-established building elements - such as window panes, façade elements made of glass or sheet metal - or even to plastic sheets with low-cost thin-film cell material. This would also make new types of structures conceivable, such as lightweight roofing made of photovoltaic textiles. Despite many years of effort, all this has been held up by complicated permitting standards for building materials, resistance from the industries concerned, the heating produced by permanently installed solar modules, the difficult electrical integration of modules differing in size, orientations and shading, and the lack of interest on the part of module manufacturers, who are enjoying fast growth anyway.

Several developments give hope for significant progress here in the coming years: Lower PV costs and climate policy requirements are increasing the pressure to develop less intrusive PV modules for buildings. Larger markets are also allowing previous niches to grow to the point where cost-effective mass production is becoming possible. The temperature tolerance of PV modules is constantly being improved, so that mechanical integration is becoming easier.

Above all, however, there are again nano-technological innovations that allow for new product concepts: Small-scale power electronics allow very different PV surfaces to be integrated. CIGS variants and organic thin-film materials that can be applied by spraying or printing are becoming increasingly efficient and stable. Last but not least, there is hope for perovskites, for which the application to various surfaces, including textiles, is being investigated.

The dual use of mechanical structures will make decentralised power generation on buildings cheaper. This could shift the balance between rooftop and centralised power plants in favour of decentralised generation on buildings. The use of roofs is increasingly being joined by the use of facades, car park roofs, noise barriers etc. Roof-mounted PV systems already require significantly less steel and cement than ground-mounted PV systems - and no additional space. However, they are more expensive per installed kilowatt because of the higher costs for installation and inverters. On the other hand, the fact that a considerable part of the electricity produced on buildings can be used in the immediate vicinity contributes to a significant advantage in the grid costs of the overall system. However, this is insufficiently taken into account in a market structure geared towards centralised production. In 2021, rooftop systems accounted for 46% of new installations worldwide, and their market grew significantly faster than that of ground-mounted systems. In China, rooftop systems accounted for more than half of new installations for the first time. However, commercial forecasts assume a roughly constant ratio for the next few years.

Both the further increase in efficiency and the reduction of the effort for mechanical support structures amount to a further saving of material and energy per unit of power. To a considerable extent, these are made possible by nanotechnological innovations.

Photovoltaics is outpacing wind energy

With these savings potentials, photovoltaics is clearly superior to other renewable energies.

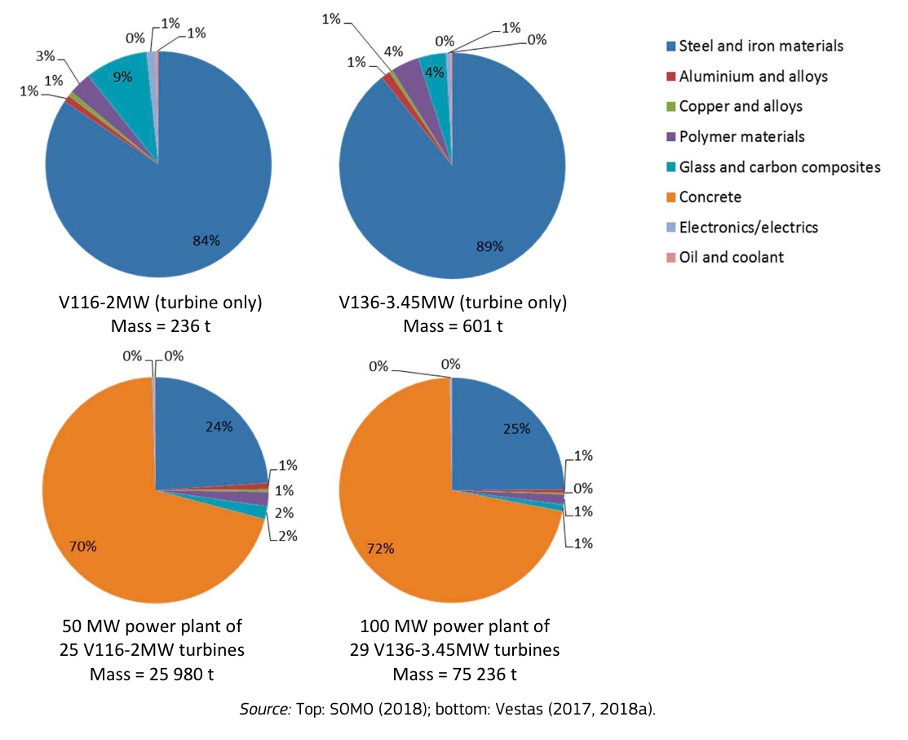

For onshore and offshore wind energy, the cost share of conventional material-intensive technologies is much higher. For a wind turbine to become more efficient, it has to be taller in order to take advantage of faster winds at higher altitudes. But that requires heavier towers. Unless the concept is fundamentally changed: It had been hoped that with kite technologies the costly towers could be avoided, but so far the theory did not work out. The nanotechnological innovation potential in wind energy is quite limited: only little can be saved by improved power electronics (see next episode of this series) or improved high-tech steel and composite blade materials.

The indications provided by life cycle analyses of the various energy sources differ greatly because many diverse parameters are taken into account and the technologies are developing rapidly, especially in the case of photovoltaics. However, combining three of the more complete analyses from recent years, some very revealing conclusions can be drawn. Comparing onshore wind with PV ground-mounted power plants shows that even a few years ago, onshore wind power plants needed about five times more cement and one and a half times more steel than PV ground-mounted power plants for the equivalent electricity production. In total - and in the case of PV power plants, glass is also a factor - wind power plants were about two and a half times heavier than PV power plants with the same annual output. And this is still the most advantageous comparison for wind power: offshore wind power plants need considerably more steel than the onshore power plants considered here. And rooftop PV systems almost completely eliminate the need for steel and cement for their own elevation. So even a few years ago (some of the figures are from before 2018), photovoltaics had a clear advantage in terms of material requirements. And this gap is widening over time: an increase in wind turbine capacity from 2 to 4 MW led to a 13% increase in steel consumption per kilowatt hour generated because of the taller towers. The cost advantage of photovoltaics will therefore only intensify over the years. All the more so as the decarbonisation of energy-intensive polysilicon production through switching from coal-fired power to solar power will be significantly cheaper than the decarbonisation of steel and cement. The slight advantage of wind power in CO2 emissions identified in most studies should now be a thing of the past, thanks to the substantial savings in silicon and energy consumption for polysilicon production.

This means that wind energy - which is very helpful as a complement to photovoltaics because the wind often blows just when the sun is not shining - will continue to lose importance compared to PV.

Overall, it can be seen that the low and further decreasing material intensity of photovoltaics renders it increasingly cost-effective compared to all other energy sources known so far. It needs no fuel, no thermal insulation, no radiation shielding, no elaborate safety systems - just surface area. It is interesting to note that life cycle analyses show that the land requirements of solar power are smaller than those of coal-fired power. At the same time, photovoltaics cause very little damage to landscapes from mining and produce no significant exhaust gases and waste. The materials can be largely recycled.

The relatively low investment required beyond the actual energy conversion process in thin semiconductor layers at the nano level can also explain the amazing scalability of photovoltaics, both upwards and downwards. When heat (all thermal power plants), radioactivity or explosive processes (nuclear energy), harmful materials (hydrogen, ammonia, methane), or hard-to-reach locations (geothermal energy, high-altitude winds) are involved, then necessary countermeasures such as insulation, shielding, safety systems, seals, towers or boreholes make large units cheaper than small ones. Scaling here always means scaling up.

In photovoltaics, scaling down can even mean saving on structural elements (e.g., with building integration). Small modular units allow standardised processes, automation and mass production with high flexibility in diverse applications. The extent to which smaller, decentralised generating units are cheaper depends on their function in the overall supply system. We will discuss the importance of reduced material requirements or an increasing decoupling of material, energy and information intensity in more detail when discussing the other energy technologies made possible by nano-science.

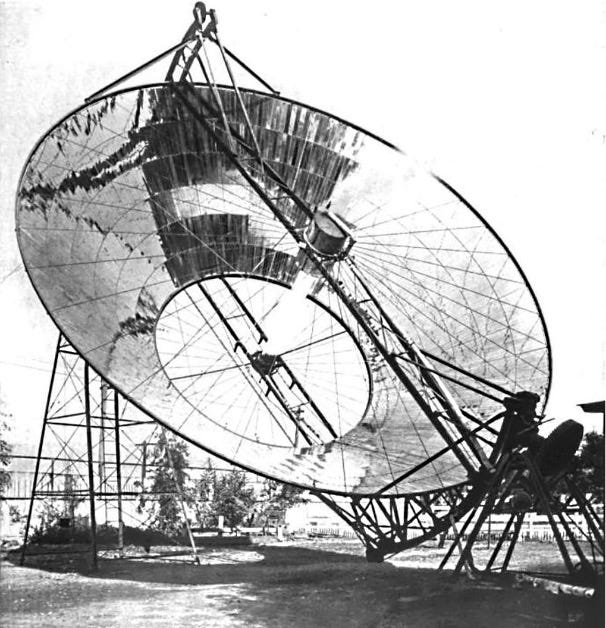

Concentrated Solar Power - a predictable flop

Since the end of the 19th century, people have been working on concentrating sunlight with mirrors, heating a liquid with it and using it in a steam engine or turbine to generate electricity. Since the 1990s, research activities on the technology, now called CSP (Concentrated Solar Power), have been intensified in the USA, Spain and Germany. The older plants, which used large round parabolic mirrors to concentrate the radiation, were joined by trough-shaped parabolic mirrors concentrating on a horizontal pipe and then by tower designs, where hundreds of electronically controlled "heliostats" are used to concentrate the solar radiation of a large area onto a receptor at the top of the tower, providing higher temperatures.

In 2009, when photovoltaics began to become competitive, large German companies founded the Desertec Industrial Initiative DII on the initiative of Munich Re (now MunichRe, the world’s largest reinsurance company), which had become aware of climate change. It set itself the goal of producing electricity in North Africa with CSP and transporting it to Europe with large cable connections. It was mentioned as a particular advantage that the heat generated can be stored for several hours with liquid salt, which would allow electricity to be produced beyond the hours of sunshine.

Siemens raved about the technology, arguing that most of the technology needed, namely the generation of electricity from heat, was already mature and proven. But that's exactly what became a problem: while around 2010 electricity from CSP power plants and PV power plants still cost about the same, CSP power plants failed to significantly reduce costs. In addition, there were persistent problems with sensitive mirrors and tracking mechanics in the harsh desert climate, as well as with the provision of cooling water. CSP had no nanotechnological innovation potential - except in tower plants in the receptors and the electronic control systems. This could have been known in advance, but the companies involved were not interested in advancing photovoltaics, which can also be used decentrally, and stuck to the material-intensive heat-power technology. The massive political support, especially from the German government, did nothing to improve matters. Years later, the DII changed course and promoted large-scale PV power plants and wind energy as generating technologies. Today, it focuses mainly on hydrogen production and names Saudi Arabia's ACWA Power, CEPRI/State Grid of China and ThyssenKrupp as "strategic partners".

The failure of CSP applies to the generation of electricity from solar radiation. For the generation of useful heat for industrial processes, parabolic mirrors can make perfect sense. However, the plants must be large enough to make the use of heat storage worthwhile. In general, for heat processes, larger units are more favourable because of the more favourable surface-to-volume ratio, as relatively less heat is lost.

Solar power costs depend on location

The cost of electricity from photovoltaic systems depends on location in a quite different way than previous energy sources. The most important factors are the following:

Solar radiation

Investment costs

Bureaucracy

Labour costs

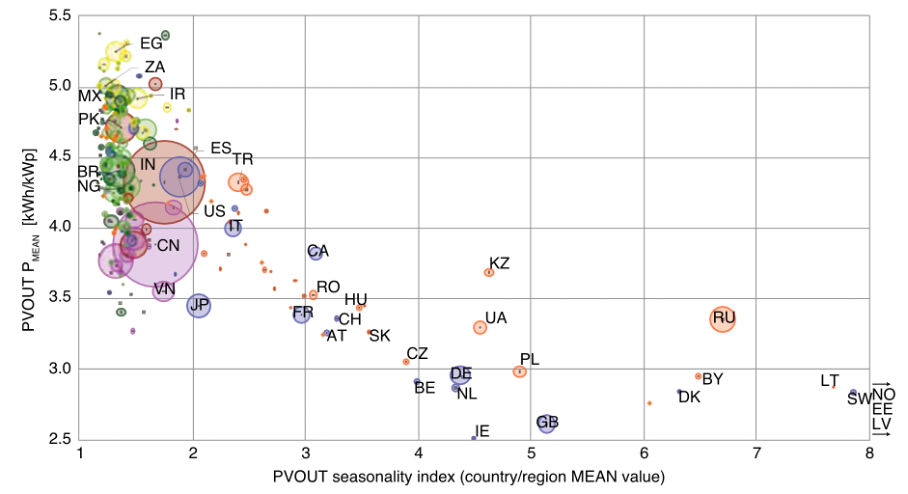

The differences in solar radiation are not as great as many people assume: In Abu Dhabi, an installed capacity of one kilowatt peak generates 1,966 kilowatt hours in a year. In Catania it is 1,525, in Berlin 1,076, in Edinburgh 960, about half as much as in Abu Dhabi.

Also surprising to many is how much the costs of solar power plants differ in different countries: in Japan they are 2.9 times as high as in India and 2.4 times as high as in Germany. This is clearly due not only to different hourly wages, but above all to the regulatory environment corresponding to different political priorities.

Combining the yield data with the costs of the power plants results in the following order for the investment costs (CAPEX) per kilowatt hour generated. European locations fare not as badly in this ranking as many assume.

Apart from the annual yield, however, another aspect of solar irradiation plays an important role. The reliance of electricity production on solar irradiation is the biggest problem of photovoltaics. With storage, flexibility in consumption, offsetting with wind power and, if necessary, transport over longer distances, the volatile electricity production and electricity consumption must be brought into harmony. We will see in the final chapters of this series the effort it would take to achieve this. If the solar radiation essentially only fluctuates between day and night, as it does near the equator, then a 24-hour storage system is sufficient to compensate for the intermittent solar radiation. However, if there are large seasonal differences, as in northern Europe, then the energy must be stored over much longer periods to compensate. In addition, strong seasonal fluctuations in solar irradiation result in larger fluctuations in consumption for heating and cooling. The "seasonality" of solar irradiation, which is given as the ratio of PV yields between the warmest and the coldest month, thus has a considerable influence on the costs of a demand-covering electricity supply. This aspect must be added to a mere consideration of the total annual yield.

These natural factors of influence are leading to a significant shift in comparative cost advantages in the international economy. If coal deposits were one of the decisive factors for the emergence of industrial centres at the beginning of industrialisation, favourable conditions for the increasingly important primary energy source, solar energy, will represent important cost advantages for energy-intensive industries in the future. We will only be able to assess the significance of this at the end of this series in connection with the prospects for the development of other energy-relevant technologies.

Photovoltaics will dominate future power supply

The major and steadily increasing advantages of photovoltaics will mean that solar power will increasingly dominate the future of energy supply. Its advantages can be summarised as follows:

PV is extremely reliable: No moving parts, no fuel, very low risks, essentially no maintenance for 30 years

PV can be mass produced, yielding classic economies of scale and learning curves

Innovation at the nanoscale is rapid and sustained: core process with high potential, simple auxiliary structures, miniaturisation, decreasing material intensity

PV is extremely scalable, up and down: Nano-level energy conversion, no thermal processes, little additional overhead

PV can be deployed quickly: Innovation cycles are ten times shorter than for conventional energy

The cost of generating electricity becomes unbeatably cheap. However, this is countered by a weighty disadvantage: electricity can only be generated when sunlight is available. Therefore, additional technologies are needed to make solar power the most important source for our energy supply. That is the topic of the next episodes in this series.

The technologies exist. But the transition requires a profound paradigm shift and a reorganisation of institutions and decision-making mechanisms that have evolved with the old fossil fuel energy supply. It will also require substantial initial investment in the transition to an energy supply which will then be much cheaper and much less damaging. In view of the climate crisis, this has to happen faster than all previous technological upheavals.

That is why it is urgent that all those involved with energy supply - as consumers, citizens, investors or other decision-makers - familiarise themselves with the broad concepts of the new options becoming available. At the end of this series we will come back to the important consequences that these changes will have for many economies and for international relations.

Minor corrections: 20.9.2023