Electrification: Electricity too expensive compared to fuels - China overtakes all

A pragmatic proposal for an easy-to-manage new European energy policy goal

China is driving the electrification of its energy system much faster and more successfully than Europe and North America. This is something to think about. Electricity needs to replace fossil fuels. But outdated taxes and subsidies are sending the wrong price signals. Europe needs to get the framework right so that end-consumer prices drive the change, rather than slow it down.

Electrification of energy consumers - indispensable for the energy transition

Over the past decade, it has become clear that we must not only reduce emissions of climate-changing gases, but that we must stop them very quickly. If we fail to do so, large parts of the world risk becoming uninhabitable. This means that the use of fossil fuels must not only be reduced, but stopped altogether. At the same time, unexpectedly rapid technological developments are opening up encouraging prospects for a sustainable and cost-effective energy supply.

Switching from fossil fuels to sustainable energy sources requires significant reorganisation along the entire production/use chain. Significant efficiency gains are possible. Electricity has been at the centre of the new energy outlook since spectacular cost reductions and performance improvements were achieved in photovoltaics (electricity from sunlight), new types of batteries (electricity storage) and power electronics (electricity conversion), and to a lesser extent in wind power and heat pumps.

Hopes that the search for non-fossil fuels would leave existing technical and economic structures largely untouched have been mostly dashed. Biomass is too valuable to be used as a fuel - we need the limited quantities available primarily as a raw material for chemicals, construction and clothing. Hydrogen as an energy carrier and synthetic fuels based on it will in most cases remain much more expensive than direct electricity use and will therefore be limited to niche applications. The efficiency of their use chains is poor for physical reasons: electricity-fuel-(transport)-electricity: less than 30%, electricity-fuel-(transport)-heat: less than 50%.

The "fossil lobby", which has managed to ensure that fossil energy is massively subsidised, is trying to save its business model by persuading governments to provide massive subsidies for the transition to a hydrogen economy — often with success. Many industrialists and private consumers are still hoping that they can simply switch their gas appliances to hydrogen — even though it is now becoming increasingly clear that this would be very expensive. Subsidies that would bring hydrogen prices close to today's gas prices are not affordable.

In the new energy world, fuels are largely disappearing. Electricity is increasingly becoming a universal energy source. The transition of consumers to electricity needs to be accelerated.

Fuels must therefore be largely eliminated. Electricity is increasingly becoming a universal energy source, and the chain of use is becoming simpler and simpler: electricity generation → electricity grids → electricity consumption. In the end, when electricity is used, it is converted into heat, movement and information.

When heat is generated from electricity, heat pumps can draw up to three-quarters of the heat needed from the environment. Heat can also be transported over short distances. Direct heat generation from geothermal energy and solar heat is therefore also likely to make an increasing contribution to heat generation — heat networks and heat storage systems will certainly play a role alongside the universal electricity system.

Electrifying the consumer side of the energy system is therefore a key part of the energy transition. It is urgent because long-lived, expensive systems — heating systems, industrial plants, vehicles — cannot be replaced overnight. Large markets need to rethink, retrain and reorganise production.

China has overtaken the US and Europe in electrification

This makes it all the more worrying that Europe and the US, which have always prided themselves on being leaders, are making very slow progress. Much slower than China, according to an analysis by RMI, an American think tank whose founder, Amory Lovins, was one of the first influential advocates of an energy transition.

In 2010, China overtook the US and Europe in terms of electricity production. At the same time, Germany began to kill off its own solar industry (107,000 jobs lost between 2011 and 2014) and China began to massively expand its own.

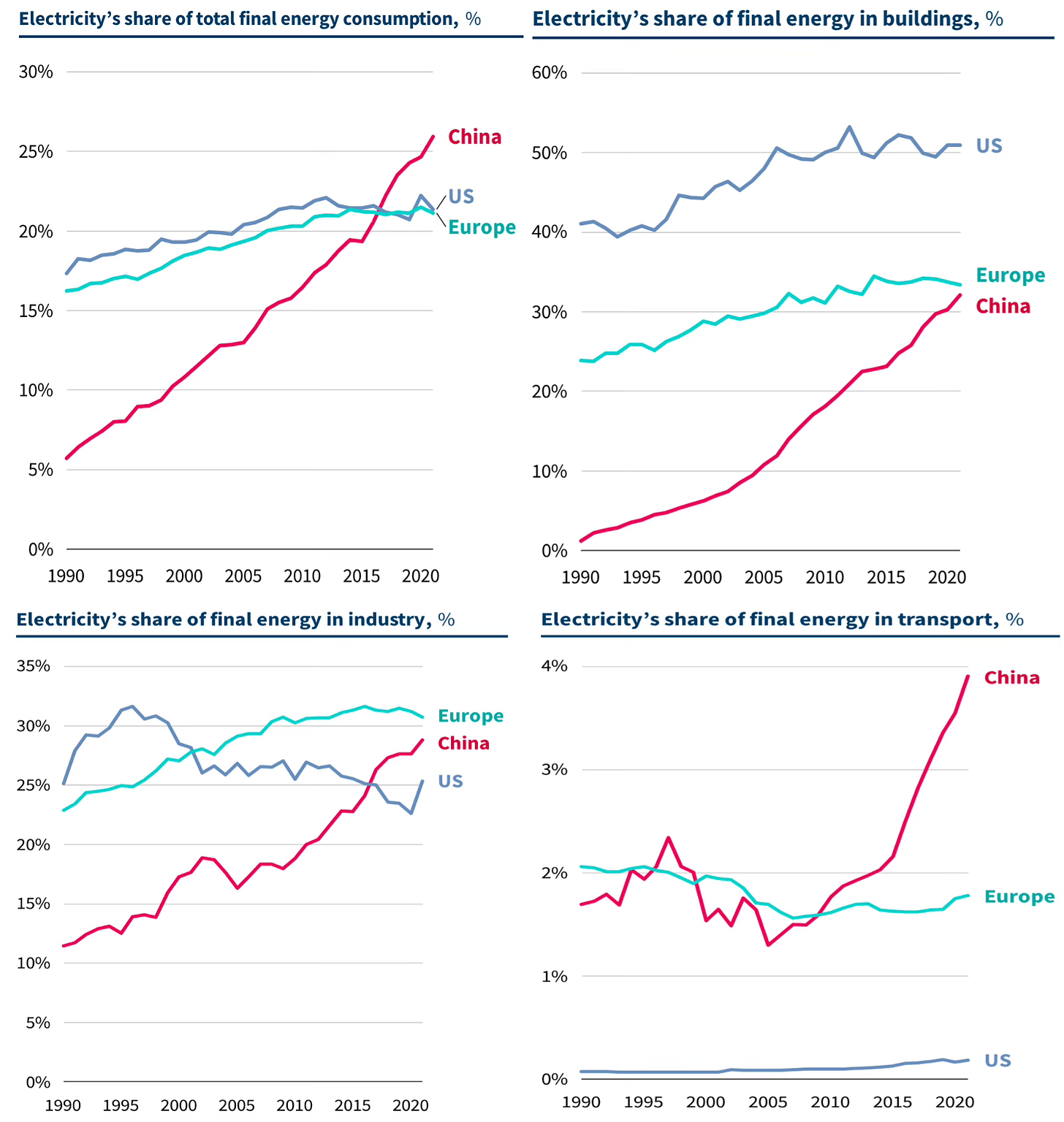

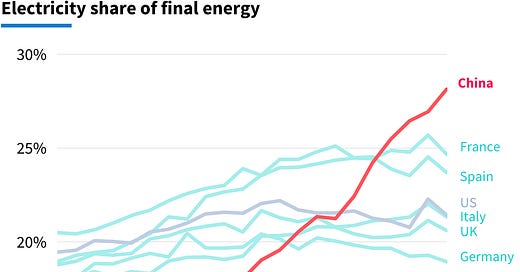

Between 2010 and 2021, electricity's share of final energy consumption will rise from 19 to 23 per cent in the US (an increase of 21 per cent), from just under 16 to 18 per cent in Germany (an increase of 15 per cent) and from 21 to just under 30 per cent in France (an increase of 42 per cent). China outperformed them all with an increase from 2.4 to 36.5 per cent, an increase of around 1400 per cent (see first chart in this post). China is therefore far better equipped for the energy transition than the major Western countries, not only in terms of photovoltaics and batteries, but also on the consumption side.

Unfortunately, detailed statistics on the composition of final energy consumption are not publicly available. However, the following graphs give an idea of how fast China is making progress in the various sectors.

The relationship between gas and electricity prices and the conversion of heat supply

The RMI attributes the impressive difference in electrification rates not least to the different price ratios between electricity and natural gas. In the USA and Western Europe, electricity is much more expensive than gas. It should be noted that the utilisation efficiency of natural gas is significantly lower than that of electricity, although this varies greatly depending on the application. For its price comparison, the RMI sets the efficiency of gas at 40 per cent of that of electricity (see graph) - electricity would therefore have to be 2.5 times more expensive for parity in utilisation. This can be calculated differently depending on the application mix, but the differences between China, Europe and the US remain. When comparing natural gas heating and heat pumps, electricity is more than three times more efficient — while only slightly more efficient in the case of direct electric heating.

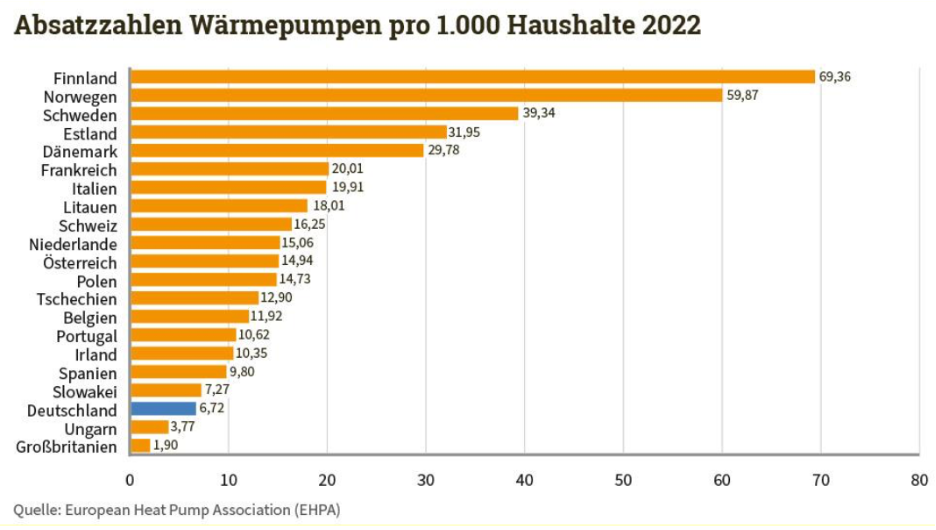

When electricity is relatively cheap, the payback period for switching to electricity is shorter. Compared to gas heating systems, heat pumps are often not yet attractive at today's electricity prices in Germany - they will only be economically viable if the likely price development is taken into account. However, many decision-makers tend to focus on current prices rather than future ones: when the German government tried to introduce a gradual, economically sensible phase-out of gas in last year's Heating Law, it met with a wall of opposition from those who think in the short term.

Let's take a closer look at gas and electricity prices in Europe using EU statistics. In the second half of 2023 — i.e. after the price wave caused by the widespread elimination of cheap Russian gas — electricity prices for households, including taxes, were on average 2.5 times higher than gas prices (i.e. the value for which the RMI assumes average efficiency parity) in the 27 EU countries. The share of taxes and levies in electricity prices was about the same as for gas. At least the ratio was already much better than in 2020, before the price wave, when electricity was on average three times more expensive and taxes and levies were 1.4 times higher for electricity than for gas.

Outdated price signals are hampering the heating transition. Electricity must become cheaper than gas.

The situation in Germany was particularly striking at the time: electricity was 4.8 times more expensive than gas, taxes and levies on electricity were 3.4 times higher - three years, an energy crisis and a change of government later, the figures last year were slightly closer to the EU average (3.51 and 1.70 respectively), but still far from good. The threshold for widespread acceptance of heat pumps is likely to be a sustained electricity/gas price ratio of around 2.5. The EU average is now at this threshold, while the German value is still much higher.

In Italy, for example, the ratio of electricity to gas prices was already 2.4 in 2020, half the level in Germany. No wonder that heat pump sales per household were three times higher in 2022.

The situation is even worse for other consumers, so-called "non-household consumers", i.e. industry, services and administration: in 2023, electricity was 3.1 times more expensive than gas, while taxes and levies were 1.5 times higher. Three years earlier, electricity was even 4.6 times more expensive, while taxes and levies were 2.1 times higher for electricity than for gas. Germany, in particular, had an extremely pro-gas policy at the time: including taxes, electricity was 6.25 times more expensive; today it is slightly below the European average. No wonder industry is hesitant to switch.

The share of taxes and levies shows the scope for policy action: On average in the EU, taxes on electricity account for 37% of non-household prices in 2023, and only 24% for gas. Shifting the tax burden from electricity to gas (which is also favoured in other ways) could trigger significant shifts in consumption in all sectors.

Key to transforming the transport sector: What does electricity cost compared to petrol and diesel?

Just as the price ratio of electricity to natural gas is decisive for the building sector, the price ratio of electricity to petrol and diesel is decisive for the speed of the switch in the transport sector.

The incomplete graphs published by the International Energy Agency give an idea of the different market dynamics for electric mobility at a glance:

The price ratio of electricity to petrol in 2023 was 0.6 in China, 1.4 in the US and 2.0 in Germany. Not surprisingly, the share of EVs in the total market in 2023 differs significantly: China 38%, Europe 21%, Germany 25%, USA 10%. At these price ratios, Europe will fall further and further behind. The Chinese industry can adapt faster. EU import tariffs won't help.

Photovoltaics drives electrification and decarbonisation of the energy system

However, electricity in China is not yet as clean as in Europe: in 2022, 65 per cent of electricity was generated from fossil fuels (EU 39 per cent, US 50 per cent) and 61 per cent from coal, which is particularly harmful to the climate (EU 16 per cent, US 19 per cent). Depending on the efficiency of the application, the switch by end users from fossil fuels to electricity therefore has only a small positive or sometimes even negative effect on today's climate impact.

But this is changing: the share of renewables in China's electricity generation is growing faster than in the US and Europe: in 2022, wind and solar power accounted for 13 per cent in China, 23 per cent in the EU and 15 per cent in the US. Based on the growth rates of the last five years, China will outperform the US in 2026 and the EU in 2032. If we take into account the acceleration in the last two or three years, it will be much faster.

Direct photovoltaic electricity generation has accelerated in recent years as solar power has become cheaper than all other forms of generation.

In terms of global investment in new electricity generation capacity, photovoltaics overtook all other forms of generation last year.

China has the highest growth rates and had a larger PV market in 2023 than the rest of the world combined. China has been outpacing all other markets for ten years now.

It should be noted that the variability of solar power generation would not be possible without the equally rapid, but somewhat delayed, advances in power electronics — which, for example, made efficient wind power generation possible in the first place — and in electric batteries. Together, these innovations are enabling a much more flexible electricity system. As with photovoltaics, China has achieved global leadership in these two technologies by setting long-term strategic priorities.

China is overtaking everyone else - not just in renewable electricity generation, but also in the electrification of energy use

These Chinese growth rates could not have been achieved without faster implementation of individual projects compared to Europe and the US. Planning and building renewable power plants and grids in China is at least twice as fast. It takes one to two years to build a solar or wind power plant in China. One reason for this is that the authoritarian Chinese state can enforce its decisions quickly. But that's not all: everyone involved understands that developing renewable energy is a high strategic priority for China, which has a much younger economy.

In Europe and the US, too, efforts are now being made to streamline outdated, encrusted structures - but progress is slow. The planning and decision-making rhythms for the old technologies were completely different: everything revolved around large power plants with long planning and construction times and fairly constant prices. Decision-making by large industrial companies was slow. Today, the new technologies allow a much more decentralised and faster approach. But the old centres of power do not want to loosen their grip on development. They try to hold on to old structures and processes and slow down change.

China's faster economic growth is making it easier to build new, innovative and agile structures alongside the old. While the old structures continue to plan coal-fired power plants, the new ones are supported by far-sighted government planning institutions with favourable framework conditions.

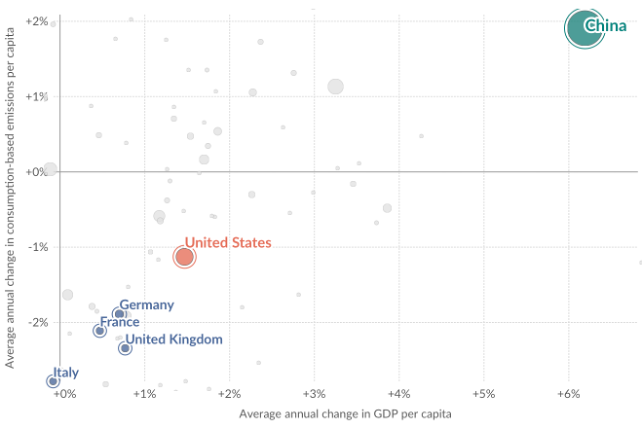

When comparing the development of climate-damaging emissions in China with the USA and Europe, population growth and the impressive increase in prosperity must be taken into account, as well as the emissions that are imported and exported with products. Over the ten years from 2011 to 2021, per capita economic output in China grew by an average of 6.2 per cent annually and climate-damaging emissions by 1.9 per cent. Compared to the USA (+1.5 per cent / -1.1 per cent) or Germany (+0.7 per cent, -1.9 per cent), this is a very comparable performance, as the following chart shows.

A comparison of China's climate change emissions with those of the US and Europe must take into account population growth and impressive increases in prosperity, as well as emissions that are imported and exported with products. In the ten years from 2011 to 2021, China's per capita economic output grew by an average of 6.2 per cent per year and its GHG emissions by 1.9 per cent. Compared to the US (+1.5% / -1.1%) or Germany (+0.7%, -1.9%), this is a very comparable performance, as the following graph shows.

As China's energy transition accelerates, Europe and the US are also likely to fall behind in their emissions reduction performance. The widespread hubris towards China in this regard is therefore completely misplaced.

Correcting the price signals for energy use: Europe must set clear targets

Without an improvement in the price relationship between fossil fuels and electricity, Europe and the US will fall hopelessly behind China in key energy technologies and will be unlikely to meet their own climate targets. In the long term, the electrification of the energy system is inevitable - the physically superior efficiencies and cost advantages cannot be permanently compensated for by subsidies. But there is no time to lose - both in terms of the pressing climate crisis and in terms of competition between economic blocs.

If the transition to electricity in China is much faster than in Europe and the US, the dominance achieved in photovoltaics and batteries, which are crucial for electricity generation, could soon extend to other technologies that enable highly efficient use of electricity. When it comes to electric cars, China seems to be getting there soon.

In market economies, where individuals' purchasing decisions are largely determined by prices, regulations and temporary incentives are unlikely to counteract mis-set price signals. In the case of energy supply, the framework conditions are largely set by policy, with subsidies and taxes determining price relationships. Four decades ago, it was the right thing to do to promote the substitution of coal with clean gas and not to waste inefficiently produced electricity from coal or nuclear heat on simple heating applications. Today, however, the price signals that were right then are clearly pointing in the wrong direction.

The price ratio of electricity to fuel must change. Today's taxes and subsidies offer sufficient scope for a correction. The EU should prescribe an easily manageable target value for Member States.

Emissions trading, which was hailed as a market-based solution to the climate problem and has been the EU's main climate policy instrument since 2005, is being used so cautiously that it is having too little effect. Moreover, it has not even been applied to buildings and transport - although this is slowly changing. In Germany, the fixed CO2 price on fossil fuels for end users (which will be integrated into the emissions trading system in 2027) was raised to €45 per tonne of CO2 at the beginning of the year. This equates to an increase of 0.39 cents per kWh for natural gas, or 4% of last year's household price - tiny progress given that electricity will be three and a half times more expensive in 2023.

The EU has set itself the target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 55% from 1990 levels by 2030. By 2050, Europe should be climate neutral. According to the calculations of climate scientists, these targets are inadequate - but it would be good to at least be on track for these too modest ambitions. The German Climate Protection Act provides for a reduction of 65 per cent by 2030 compared with 1990. From 2023 to 2030, a reduction of 32 per cent is still required. This target cannot be achieved with current policies. Even decarbonising power generation is not enough. Additional measures are needed. Above all, people need to understand what these targets mean for them.

I believe that it would be useful for the EU to adopt an additional target for its energy policy as soon as possible:

Member States are required to ensure that the price of fuels - natural gas, domestic heating oil, petrol, diesel, but also hydrogen and e-fuels - is at least 70% of the price of electricity for both households and nonhouseholds by 2030.

For most products, the tools for verification are already available: EU price statistics, measured in euros per kilowatt-hour, including taxes and levies. Electricity should therefore cost on average no more than 1.43 times the price of natural gas, which is roughly in line with the current situation in China, but requires considerable effort compared to the EU average of 2.5 times. How this would be achieved in the Member States would depend on the national frameworks, which are still very different and would presumably be harmonised. A much more restrictive approach to EU emissions trading - whose consequences are difficult for citizens to understand - would be a helpful European measure.

With such a target, households, trade and industry would have planning security: they would know that electric-based technologies would soon be significantly cheaper to operate for most applications that are still powered by fossil fuels today. This would trigger a surge in innovation and investment immediately after the decision, but would also allow for flexible transitions.

In addition, regulation and support will still be needed to make the transition bearable. However, the main driver of change would be market forces, which would no longer be driven in the wrong direction.

Europe must face reality. The climate crisis and international competition demand decisive action. Europe's traditional strength — high-quality system technologies — must be developed for the future. Focusing on luxury goods, tourism and financial products is not an alternative.

great! just back during the nigth from BEIJING and able to confirm enormous advancements of batteries -- carmakers on '' electrification'' !

grazie Ruggiero !