Renewable energies shift international competitive advantages

Sunny locations will gain an increasing advantage in energy costs. Europe must think carefully about which industries it wants to expand, retain or abandon, and in which regions.

Translation from the German original by Dr Wolfgang Hager

In Europe, and particularly in Germany, industry lobbies are calling for subsidies to cope with high energy costs. Energy-intensive industries are already enjoying considerable advantages at the expense of the public and the rest of the economy. The transition to renewable energies will shift the cost ratios internationally: Europe is increasingly at a disadvantage in terms of energy costs compared to sunny locations. Offsetting this with subsidies would be very expensive. Europe needs to think carefully about which industries it wants to expand, retain or abandon, and in which regions.

During its industrial rise, Europe was blessed with local cheap coal. More than a century later, oil was imported via ships and pipelines — mainly from the Middle East. And then gas was added, at first domestic, then mainly from the Soviet Union. During the past five decades, the EU has met more than half of its energy needs with imports. In Germany, the share of imported energy in total consumption rose from 12% to 50% between 1960 and 1979. Shortly before the Ukraine war (2019), a quarter of the EU's total energy consumption was met by imports from Russia. Germany in particular, has secured cheap Russian natural gas by building pipelines since the 1970s.

But that is now a thing of the past. With the transition to a sustainable energy supply based primarily on electricity, especially solar and wind energy, competitive advantages are shifting globally. This will inevitably have huge consequences for the international division of labour.

Energy-intensive industries in Europe

During times of comparatively cheap energy, an energy-intensive and politically influential heavy industry could develop in Europe. In 2021, the EU industry consumed around 37 per cent of electricity and around a quarter of all energy end-use.

Looking more closely at industrial energy consumption in Europe, two aspects stand out: First, Germany is by far the largest industrial energy consumer. Second, just a few sectors consume most of this energy, while their share of employment and value added is low.

In Germany, the "energy-intensive industries" as defined by the statisticians consumed 77% of the total amount of energy used in industry in 2021, but only contributed around 17% to industrial value added and 15% to industrial employment.

And these are still rather broad categories: if one looks at individual stages of the value chain within these sectors (chemical and metal industry, coking, refineries, glass, ceramics, paper and cardboard), such as basic chemicals, then the contrast between the high shares of energy consumption and modest contribution to gross value added and employment is even more striking. However, there we have hardly any publicly available data. According to an EU study, the share of energy in total costs of production varies between 3.7 and 14.3 per cent within the basic chemicals sector in the next more granular level of classification.

Energy-intensive industries in Europe contribute surprisingly little to employment and value creation

Typically, the first processing steps of raw materials are particularly energy-intensive: from iron ore to pig iron, from crude oil/natural gas to basic chemicals, from wood to mechanical pulp, from quartz sand to molten glass, from bauxite to aluminium. These resulting standard semi-finished products (pig iron, raw aluminium, basic chemicals) are often less expensive to transport than the raw materials and are internationally traded.

In the new circumstances, the question thus arises as to where it would make sense to relocate these energy-intensive production stages, which anyway generate relatively little employment and added value, to regions where energy costs are lower. To do this, it is helpful to first estimate more precisely how energy cost ratios will develop. This is not easy, as a variety of taxes, subsidies and unsubstantiated claims by special interests tend to cause confusion.

Solar power will dominate future energy systems

In a previous Spotlight I explained why photovoltaics (PV) will overtake all other energy generation technologies in the long term. For a long time, photovoltaics were underestimated and continue to be underestimated in influential models of the global energy system, such as those of the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the IPCC, on which the recommendations of the world climate conferences are based.

In 2022, a network of researchers from 16 universities in 9 countries published a comprehensive history of energy system modelling, especially of scenarios with 100% renewables. It shows how much the global share of photovoltaics has increased in the hourly cost-optimised model calculations for 2050: in the latest optimisations, it reaches 70 to 80 percent of electricity production, which by then will account for the vast majority of energy consumption. The reasons for steadily growing PV shares are that costs are falling faster than expected: both for the PV systems themselves and for coping with their fluctuating power generation. The latter is benefiting from ever-cheaper batteries, cheaper electrolysers, better demand management options and improved linkages between the currently still largely separate electricity, heat and transport sectors. Scenarios positing lower PV shares, such as those of the IEA, arrive at a different mix and higher total costs not only because of outdated cost estimates but often because high shares of legacy energy sources are predetermined — supposedly to allow for greater diversification.

Sharply falling costs for photovoltaics, batteries and power electronics are changing the model calculations: PV is becoming the dominant global energy source

As the share of PV increases, the overall cost of energy will fall. Until recently, it was assumed that a climate-friendly transformation of the energy system would take a lot of money. Now it is becoming clear that it is at least cost-neutral if not actually saving money — although not to the same extent everywhere.

Flexible networks become a key to survival

Understanding the energy system and assessing basic options has become more difficult. It is no longer a question of relatively simple, isolated supply systems and supply chains: oil for cars, gas for heating, coal and nuclear for electricity. The future supply will be based primarily on electricity generated from solar and wind, which fluctuates over time and can only be stored with some effort. To cope with this, we will need networked systems that can react flexibly to fluctuations in production and consumption. New energy conversion and information processing technologies will make it possible to link the traditional sectors of electricity, heat and transport and involve many more decision-makers, producers and consumers, in the flexible management of a networked energy system.

The new technologies offer great opportunities for coping with the challenges of the climate crisis - but to do so, we have to learn to think in terms of flexible, networked systems

The complexity of the energy system can only be analysed in detail using elaborate models that incorporate thousands of assumptions and metrics. Defenders of the old energy economy or advocates of particular technologies are seeking to exploit this for their purposes: They present opaque calculations with questionable assumptions. Or promise a return to the older simpler world with apparent panaceas (nuclear power! hydrogen! fusion!). We should not be put off by the increasing complexity. With a few basic insights, the interplay of various innovations can be understood well enough for the most important consequences to become readily apparent. In the following, I will try to show step by step how, on the one hand, increasing networking can reduce costs and expand the scope for action, and how, on the other hand, the new technologies are causing a global shift in competitive conditions

Significant geographical cost differences for solar power

How will the coming dominance of solar power as an energy source affect future energy prices in different countries? Let's first try — as a thought experiment — to estimate how much more expensive a purely solar power supply for a large industrial plant in Germany would be compared to sunnier countries.

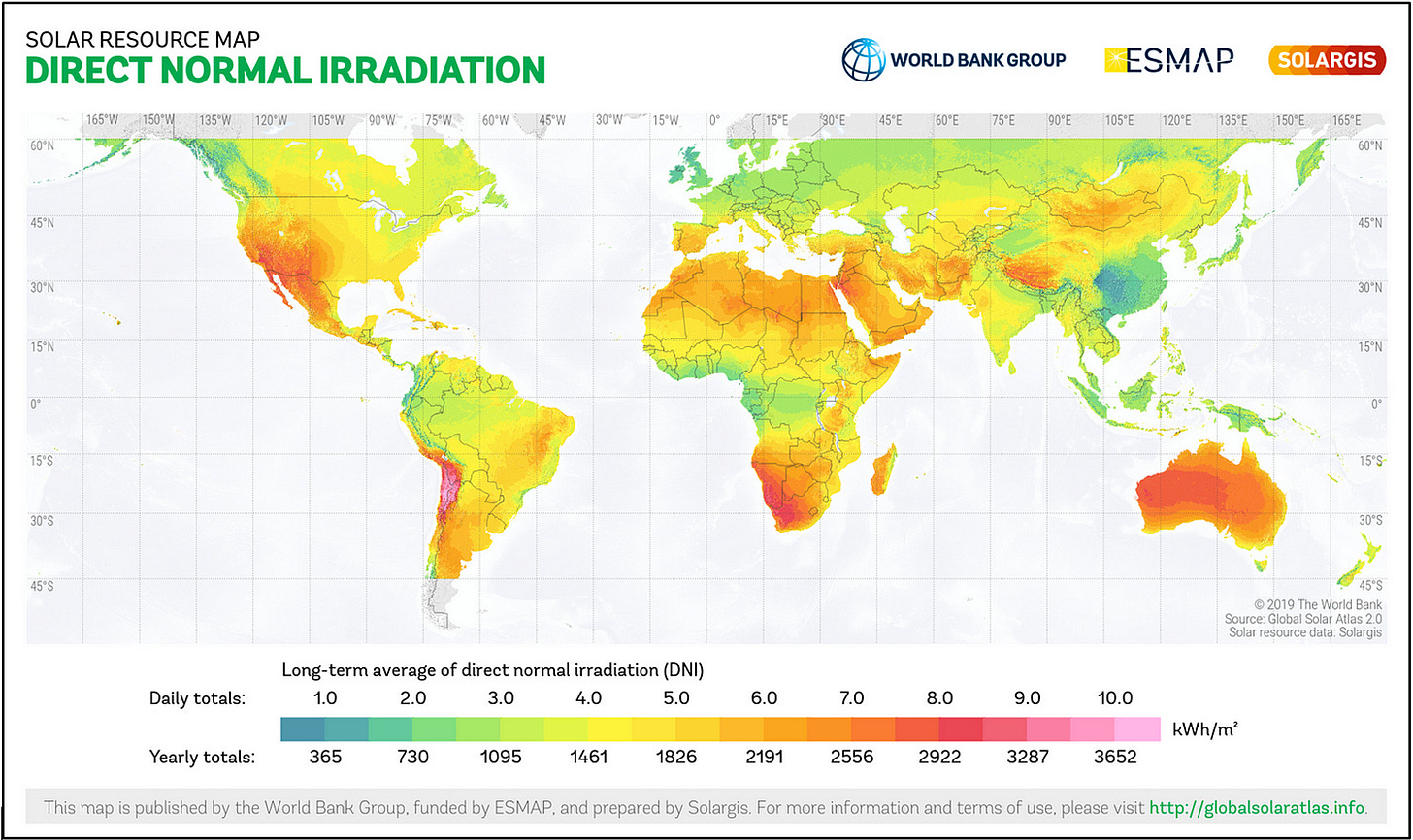

The most obvious factor is that the sun shines more intensely near the equator. However, the world map of solar irradiation shows that latitude is not the only factor that matters. Humidity, clouds and air pollution can significantly reduce the actual amount of incoming radiation.

The total annual radiation in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is twice as high as in Germany. However, the electricity yield is only 1.7 times higher, mainly because the panels become dirtier and the performance of PV cells decreases at high temperatures. However, as temperature sensitivity decreases and progress is made in cleaning, tracking and grid integration, the advantage of southern locations will continue to grow in the future.

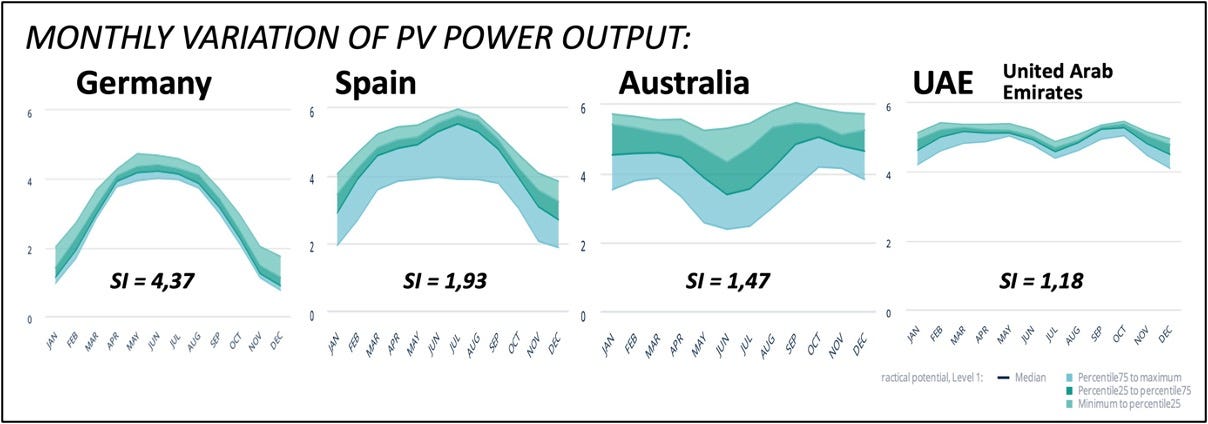

The day/night rhythm is similar in all climate zones. It can be compensated with storage, which incurs additional costs but has little impact on competitive conditions. By contrast, the difference in seasonal fluctuations is significant: the closer to the equator, the less pronounced they are. This factor is often underestimated. This particularly affects energy-intensive industries in northern latitudes, which cannot simply switch off capital-intensive plants for months on end and are therefore reliant on electricity in winter, even if it is more expensive.

If a large chemical plant were to be supplied entirely from its own photovoltaic power plant in combination with night storage (which of course, see below, nobody would do in this simple manner) and the power plant were designed to guarantee continuous production of the factory even in winter, then it would not only have to be 1.7 times as large in Germany as in the UAE (due to the lower average solar radiation) but 4.2 times as large (due to the much lower radiation in the darkest month).

Now, an attempt could be made to compensate for the seasonal difference in northern latitudes by storing the locally generated electricity for many months. Today, the only option for this is storage in the form of hydrogen in salt caverns.

In seasonal storage with hydrogen, the electricity is used to split clean water into oxygen and hydrogen in electrolysers (energy efficiency 67%), then the hydrogen has to be stored in salt caverns under high pressure (efficiency 93%) and then converted back into electricity in underutilised generators (efficiency max. 58%). This means that only 36% of the electricity stored in the form of hydrogen in summer can be used in winter. And this is based on rather optimistic efficiency assumptions for the year 2030.

Due to this low efficiency of seasonal storage, the consistently usable solar electricity yield in Germany is 20 per cent lower than the average. The consequence: even with hydrogen seasonal storage, a purely solar-powered, continuously running industrial plant in Germany would need a PV power plant 1.9 times larger than in the UAE (not needing seasonal storage).

This estimate of efficiency is quite reliable. In order to calculate the electricity costs, the estimated cost of developing the required systems would also have to be added. In the north, the high technical costs for seasonal storage with hydrogen affect the calculation. On the other hand, the financing costs can be assumed to be different in different countries. As a result, for a broad range of assumptions, the costs for continuous solar power from an off-grid system in Germany would be more than twice as high as in the UAE, Spain or Turkey.

Combination with wind power results in a more stable supply and therefore lower costs

However, wind energy is significantly less seasonal than solar irradiation, and there is plenty of it in central and northern Europe. At first glance, both offshore wind power and onshore wind power can therefore be expected to require much less effort to balance fluctuations than photovoltaics. However, because wind is much more difficult to predict than solar radiation, the storage costs can only be estimated by considering long-term weather data. It is of great importance that sun and wind generally complement each other well in most regions: When the sun is not shining, the wind blows all the stronger, both during the day and throughout the year. This is why all calculation models for a fully renewable supply rely on a (regionally different) mix of photovoltaics, offshore and onshore wind energy when optimising the energy system. Despite significantly higher costs — according to an estimate by Fraunhofer ISE, offshore wind power in Germany will cost three times as much as solar power in 2030 — the complementarity of wind and solar power can significantly reduce overall costs.

A continuous power supply for industry from captive power plants would be 75% more expensive in Central Europe in 2050 than in the United Arab Emirates and 55% more expensive than in southern Spain. Hydrogen would cost two thirds or one third more.

There are not many studies on the future costs of supplying a stand-alone industrial plant with steady renewable energy around the clock. The most convincing figures I could find come from a study published in 2020 by Finland's Lappeenranta University of Technology (LUT), which has developed the most generally accepted model for calculating energy futures. For a high-resolution grid of locations on all continents, the baseload supply was optimised with a combination of photovoltaics, onshore wind energy and storage technologies (other studies show that the addition of offshore wind would have only marginally changed the results). The world maps calculated in this way (see figure, below) show that in 2050 the costs of a continuous electricity supply in Central Europe (inland, not on the coasts) will be around 75 per cent higher than in the UAE and around 55 per cent higher than in southern Spain.

Assuming a permanent supply of hydrogen to industry (e.g. for steel production), the differences between the various locations are somewhat smaller because the re-conversion of the hydrogen from storage is no longer required: in 2050, a continuous supply of hydrogen in Central Europe is likely to cost around two thirds more than in the UAE and one third more than in southern Spain. In terms of kilowatt hours, hydrogen is slightly more expensive than electricity.

Studies sponsored by industry come to different conclusions. For example, the consulting department of the Institute of German Business (IdW) recently claimed that a continuous electricity supply ("base load product") from offshore wind power in Germany in 2045 would (only) cost 30% more than from photovoltaics in the UAE, and deducted from this the need for an electricity price subsidy. Photovoltaics was not analysed. Both the choice of technologies and the cost assumptions do not convince.

For example, they assumed that investment costs for PV would fall much more slowly than for offshore wind: Both by 2030 (26% vs. 40% compared to the actual costs in 2021) and in the subsequent period 2030-2040. This contradicts independent studies (see my earlier Spotlight). In addition, no tracking was assumed for PV in the UAE, which is crucially important there.

The background to these skewed calculations: For years, large-scale industry has campaigned intensively for offshore wind energy and mobilised a wide range of public investments for this purpose. For a while, the impression was created that offshore wind power could be achieved without subsidies - however, this is no longer the case given increased material costs. Widely believed unfair comparisons do not take into account a significant cost component: offshore grid connection. In the EU, this cost falls on the transmission grid and is paid for by electricity customers via the grid fees. On an installed capacity basis, these costs alone (over 1000€/kW) exceed the investment costs of ground-mounted PV systems.

Up to this point — in the first steps of our optimisation — we have considered stand-alone systems where large industrial plants are permanently supplied from their own power plants and storage facilities. The LUT study cited above showed that allowing small fluctuations in output (which is usually possible even for energy-intensive industries) can significantly reduce the cost of electricity supply: 9% fewer full-load hours in Germany results in 10% lower electricity costs (12% in the UAE). This would not improve the competitiveness of a location in Central Europe. However, the calculation shows that costs can be significantly reduced by combining the industrial plant with electricity consumers that have a load profile that is better adapted to the variable supply.

Grid integration can further reduce the costs of a continuous industrial power supply

For this reason, a simulation of the entire energy system is more meaningful for estimating the cost development. In December, the LUT presented a study with transformation scenarios for the entire European energy system based on its model. In the moderate scenario (complete decarbonization by 2050), the extensive optimization calculations show that it is advantageous for Europe as a whole to generate the vast majority of electricity (which will then supply almost all energy) using photovoltaics (a good 60%). Wind accounts for 33%, a third of which is offshore. In Germany, too, well over half of the electricity is to be generated by solar power in 2050 (see figure).

The fluctuating electricity generation from sun and wind is primarily compensated for by the fact that over a third of the electricity is used for electrolysis which does not require continuous operation. The hydrogen obtained is largely used to produce synthetic fuels. It is not converted back into electricity.

Electricity and heating costs will fall significantly in Europe - but more slowly than in sunnier regions.

The resulting impact on the evolution of costs is impressive. Compared to 2020 (i.e. well before the war in Ukraine), electricity costs in Europe will fall by 55% by 2050. Heating costs will fall by 27%. These would be significant cost reductions for industry. However, the costs of the entire European energy system would only fall by 8% because energy costs in the transport sector would rise - in contrast to electricity and heating costs.

Given the high costs of the synthetic fuels which are assigned a large role in these scenarios, this is hardly surprising. However, whether the assumed technology mix on the consumption side is still realistic needs to be re-examined from today's perspective. I would assume that road transport in particular will be electrified much faster and thus become cheaper. In intercontinental sea and air transport, however, energy costs are likely to rise significantly (and stay high as long as direct electrification is not possible). This may well lead to a doubling of intercontinental transport costs in container transport and slow down intercontinental trade.

A significant rise in energy costs in shipping and aviation could slow down intercontinental trade

Instead of using it as synthetic fuel, the hydrogen produced could be used as a raw material in the chemical and steel industries — this area of demand was not covered in the study. The approach of compensating for fluctuations in electricity generation with hydrogen production for non-energy use appears to be the right one: other studies also conclude that the flexible production of hydrogen for non-energy uses makes sense and can stabilise the system.

Less sophisticated models focusing on Germany arrive at lower PV shares: DIW 2021: 25%, Fraunhofer-ISE 2021: 32%, Energy Watch Group 2021: 39%. The differences are mainly due to different consumption assumptions, cost assumptions and system boundary definitions, but all point in the same direction.

We can therefore assume that the future costs of a renewable electricity and heat supply for industrial companies in Germany will be significantly lower than they are today.

By enhancing flexibility, grid integration of the industrial power supply will shift the technology mix further in favour of photovoltaics. This is likely to worsen the competitive position of Central Europe compared to sunny regions.

Hydrogen imports would exacerbate cost disadvantages

For some years now, there has been much hype surrounding hydrogen, which has been fueled primarily by the gas industry. The literature shows a wide range of cost figures that are not easy to verify. Many studies are not transparent and sometimes include subsidies. Solid empirical data on the handling and transport of hydrogen are difficult to obtain, as hydrogen has so far mainly been produced from natural gas within large industrial complexes and thus only transported over short distances.

Hydrogen has much less favourable properties for transport and handling than natural gas: the energy content of a given volume is only one-third. The molecules are eight times lighter and much smaller. They render steel brittle and require particularly dense materials for sealing. Pipes and pumps must be designed much larger for hydrogen and require different materials. Because the boiling point is minus 252 degrees (natural gas: -162°C), the liquefaction and storage of liquid hydrogen is much more complex than that of liquid natural gas (LNG). The much-discussed transport in the form of liquid ammonia (boiling point -33°C) entails significant conversion losses and requires high safety precautions due to its toxicity.

Nevertheless, the hydrogen lobbyists have been very successful. The national and European strategy papers envisage huge quantities of hydrogen. However, enthusiasm is already waning among experts. The most recent study by the global industry association Hydrogen Council from November 2023 estimated the expected hydrogen costs to be 30 to 65 per cent higher than the previous study a year earlier. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that hydrogen will play an important role in the future, if only for the chemical industry.

The German National Hydrogen Strategy (as of 2023) assumes an annual demand of 90 to 130 TWh (2.3 to 3.3 million tonnes) of hydrogen by 2030, of which 50 to 70 per cent is to be imported. To this end, huge LNG terminals are now being built with government guarantees that are supposed to be "hydrogen-ready" — something that no private investor would finance given the uncertainties regarding demand and technologies and the considerable additional costs.

This raises the basic question of how expensive imports would be. The aforementioned Hydrogen Council study enthuses about international trade but makes no mention of transport costs. In its Global Hydrogen Review 2023, the IEA compared the import of hydrogen with local hydrogen production in north-west Europe: For 2030, it expects production costs of just over 3.1 dollars per kilogramme of hydrogen in NW Europe and 21% less in North Africa. Transported by pipeline, North African hydrogen would be 6% cheaper than hydrogen produced locally in NW Europe according to the IEA model; shipped in the form of ammonia, it would be 50% more expensive, and 63% more expensive than liquid hydrogen. Latin American hydrogen would be 33% cheaper to produce but would cost between 37% (ammonia) and 72% (liquid hydrogen) more including transport. The IEA's calculations are not transparent.

A much more detailed analysis by LUT, also from 2023 and backed up by extensive literature analyses, examined hydrogen imports from Morocco and Chile to Germany. It concludes that green hydrogen from Morocco will be around 80 per cent more expensive than local production in 2030 and will still be 40 to 50 per cent more expensive in 2050, making it unattractive. With additional costs of just under 50 per cent in 2030 and just over 50 per cent in 2050, the situation is no better for hydrogen from Chile. According to the LUT analysis, if existing pipelines could be converted for hydrogen, it cannot be ruled out that imports from Morocco would be economically viable - further studies would have to be carried out to confirm this.

The differences to the IEA study result from the fact that the LUT estimates the production costs of H2 significantly lower and the pipeline transport costs (with capital costs of 7%, for 2030) four times as high as the IEA. Other independent publications also suggest that the IEA massively underestimates the pipeline costs. A detailed study by IRENA (International Renewable Energy Agency) calculates similar transport costs for new pipelines as the LUT but considers it entirely possible that existing gas pipelines from North Africa could be converted to sufficient capacity.

Actually, the transport costs depend heavily on the pipe diameter and the capital costs, as well as on the question of how well existing gas pipelines can be converted to hydrogen, with which there is hardly any experience — thus leaving much room for speculation.

The interests backing a strong international hydrogen trade are massive: it is not just the gas industry that is hoping for a successor business when natural gas comes to an end. The shipping industry is also exerting pressure: in 2018, fossil fuels and liquid chemicals accounted for forty per cent of global maritime transport — the loss of these markets would hurt. It's no wonder that the interested industry is hardly providing any cost information and is pushing for public support.

Hydrogen imports will remain more expensive than locally produced hydrogen. They are not a suitable means of offsetting the energy cost disadvantages for industry in Central Europe.

If we consider the cost of electricity generated from imported hydrogen, some popular dreams become completely implausible: compared to the average electricity costs of just under 4 ct/kWh calculated by the LUT for 2050, electricity generated from imported Moroccan hydrogen at over 30 ct/kWh would only be an option for rare peak loads. Burning ammonia imported from Chile directly would be somewhat cheaper.

The fact that the German government has decided to tender 10 GW of "H2-ready gas-fired power plants" as part of its power plant strategy, which are to "switch completely to hydrogen between 2035 and 2040", raises false hopes. As we have seen above, the reconversion of green hydrogen into electricity in the integrated system makes no sense, yet the interim report of the German system development strategy states that "hydrogen could also replace natural gas in the electricity sector at an "early stage".

What could become attractive, however, is the import of H2-to-X products such as ammonia, methanol and e-kerosene for the transport sector and material use. This would actually mean relocating the initial processing stages to sunny regions.

We can therefore conclude that imported hydrogen would be as expensive in Germany as locally produced hydrogen, even under optimistic assumptions. Hydrogen imports are therefore not a suitable means of offsetting the energy cost disadvantages of industry in Central Europe.

This allows us to draw a firm conclusion from all the above: In the medium and long term, the energy costs for industrial applications in Central Europe will be significantly more than half again as high as the energy costs in regions favoured by the sun. Even compared to the southern edge of the EU, the additional costs for electricity will be over 50%.

In the medium and long term, the real energy costs for industry in Central Europe will be significantly more than half as high again as in sunny regions

For business and politics, this is an important and far-reaching consequence of the climate-imposed phase-out of fossil fuels and foreseeable technological developments. It calls industrial structures and power relations into question. The public is hardly aware of this.

Energy-intensive industries: Relocations are indispensable for Europe to remain a manufacturing base

The future cost disadvantage of Central European locations compared to regions with low energy costs — including locations in Spain, Greece and southern Italy — can be considerable for some products. There are growing calls, particularly in Germany, to discourage the relocation of production by subsidising industrial electricity. That would be a bottomless pit. Germany's Economics Minister Habeck has proposed a "bridging electricity price" until favourable renewable energies bring down the price of electricity. This is window dressing, because with a good energy policy, the price of electricity will fall, but even faster elsewhere.

Energy-intensive companies are already being subsidised by all other electricity consumers — private households, small and medium-sized enterprises and the rest of industry. Although the official wholesale energy prices are determined on the exchange, the electricity suppliers conclude non-transparent long-term contracts with large companies. Grid costs and other levies are the responsibility of politicians, who deliberately favour energy-intensive industries. In addition — and not just since the last energy crisis — there are targeted subsidies for various reasons. There is an astonishing range of industrial electricity prices in Germany: A survey of large energy-intensive companies in 2018 revealed differences of up to a factor of three.

Perpetuating the current industrial structure with subsidies would be extremely costly, especially as some production processes will have to be fundamentally restructured to move away from fossil resources. In the production of steel, cement and basic chemicals in particular, coal, crude oil and natural gas are used not only as a source of energy but also as raw materials. In addition to the actual energy consumption of industry in the EU today (measured in energy units), around one-third is used as material input. In the chemical industry, 2.5 times more oil and gas is used as a raw material than is required for energy use. To replace these raw materials, hydrogen from electrolysis and CO2 extracted from the air are the most probable sources to be used in future — this requires a lot of electricity. The German chemical industry estimates that the sector's electricity requirements after the energy transformation (including hydrogen production) will be roughly equivalent to today's total electricity consumption in Germany (biomass utilisation could reduce demand by a maximum of one-third).

Perpetuating the current industrial structure with subsidies would be extremely costly

Who is going to pay? Industry associations and trade unions are calling for "competitive" industrial electricity prices.

The German government's integrated system development strategy is based on "the energy demand that can ensure the preservation of the existing industrial structure (including basic industries) in the future". The calculated hydrogen demand of industry alone corresponds to today's total electricity consumption.

This cannot work in view of the competitive disadvantages in terms of energy costs alone. Consumers and the rest of the industry would have to subsidise the basic materials industry, which is located here for historical reasons. The entire business location would suffer. Of course, in some cases, it makes sense to leave some production facilities at the old sites, e.g. because the cost advantages of integrated production compensate for the increased energy costs. But leaving everything as it is across the board is irresponsible. The question of whether and where we can manage with less material input is raised in the environmental debate, but not in the energy debate. At the same time, completely new questions are emerging: IT companies are reporting considerable additional power requirements (and corresponding waste heat) for the explosive growth in artificial intelligence — where and how can this be efficiently integrated into the energy supply systems?

Europe needs to think carefully about which industries it wants to expand, retain or abandon, and in which regions.

With the subsidies required to maintain the production of basic materials, far more added value, skilled jobs and strategic industrial advantages could be created in other areas. The sustainable production of many raw materials can be achieved more cost-effectively in Spain, Greece, southern Italy or Turkey. And even if internationally traded raw materials were to come from distant, sun-rich countries, the dependence on individual suppliers would be much less problematic than our dependence on a few oil and gas suppliers during the past decades, given the wide geo-availability of abundant levels of sunshine.

Some hope to avoid the problems by trying to delay the energy transition and the conversion of industry. This is an illusion — the cost advantages of solar energy supply are driving the transition and the shift in competitive advantages worldwide. Australia, Spain and India, among others, are working on large-scale projects to produce green steel and fertilisers using green hydrogen. The recent slowdown of such projects due to falling natural gas prices is a temporary phenomenon as fossil gas has to be phased out.

In order to prepare Europe's industrial structure for the new energy world, we need a differentiated vision of which production stages should be kept in place and which should be relocated to more favourable locations and regions. Only then should strategies for public support for adaptation be developed. National strategies should be integrated into an overall European concept. In view of increasing competition between continental blocs and shifting competitive advantages, it is becoming increasingly important to utilise synergies between EU countries in a targeted manner.

The changing framework conditions make structural changes unavoidable. It is negligent and cowardly to pretend to workers and citizens that everything can remain as it is. With timely adjustments, however, relocations in the basic materials industry will not have a strong social impact due to their low employment effect — far less than the foreseeable massive slump in the auto industry which has resisted timely adjustment.

As we have seen, more than ever before, energy and industrial policy means thinking in terms of networked systems. Sectoral thinking is no longer adequate to respond to the challenges of the climate crisis and technological development. Not only do the energy sectors of electricity, heat and transport need to be considered together, but now the production of raw materials also needs to be included. The chemical industry, with its integrated production facilities and co-products, is already more advanced in terms of networked thinking — however, the phasing out of fossil raw materials means that it is perhaps facing the greatest challenges. Individual industrial sectors in which the energy transition requires particularly far-reaching changes, such as the chemical, steel and transport industries, will be examined in more detail in future Spotlights. Both the changes to our environment and new technologies require far greater attention to the geospatial dimension than we have been used to in recent decades.

For an honest and forward-looking discussion, however, we also need better, publicly accessible information. The lack of detailed data on production structures, energy consumption, technologies, value creation, prices paid and material flows at the various stages of production hinders the development of realistic transformation scenarios. European statistics need to be significantly improved here. Only with a well-informed public can joint decisions be made that benefit everyone.

Time is of the essence. Europe's industry is neither fit for climate change nor for the rapidly shifting international competitive conditions. A more nuanced European debate on the future of industry is urgently needed.